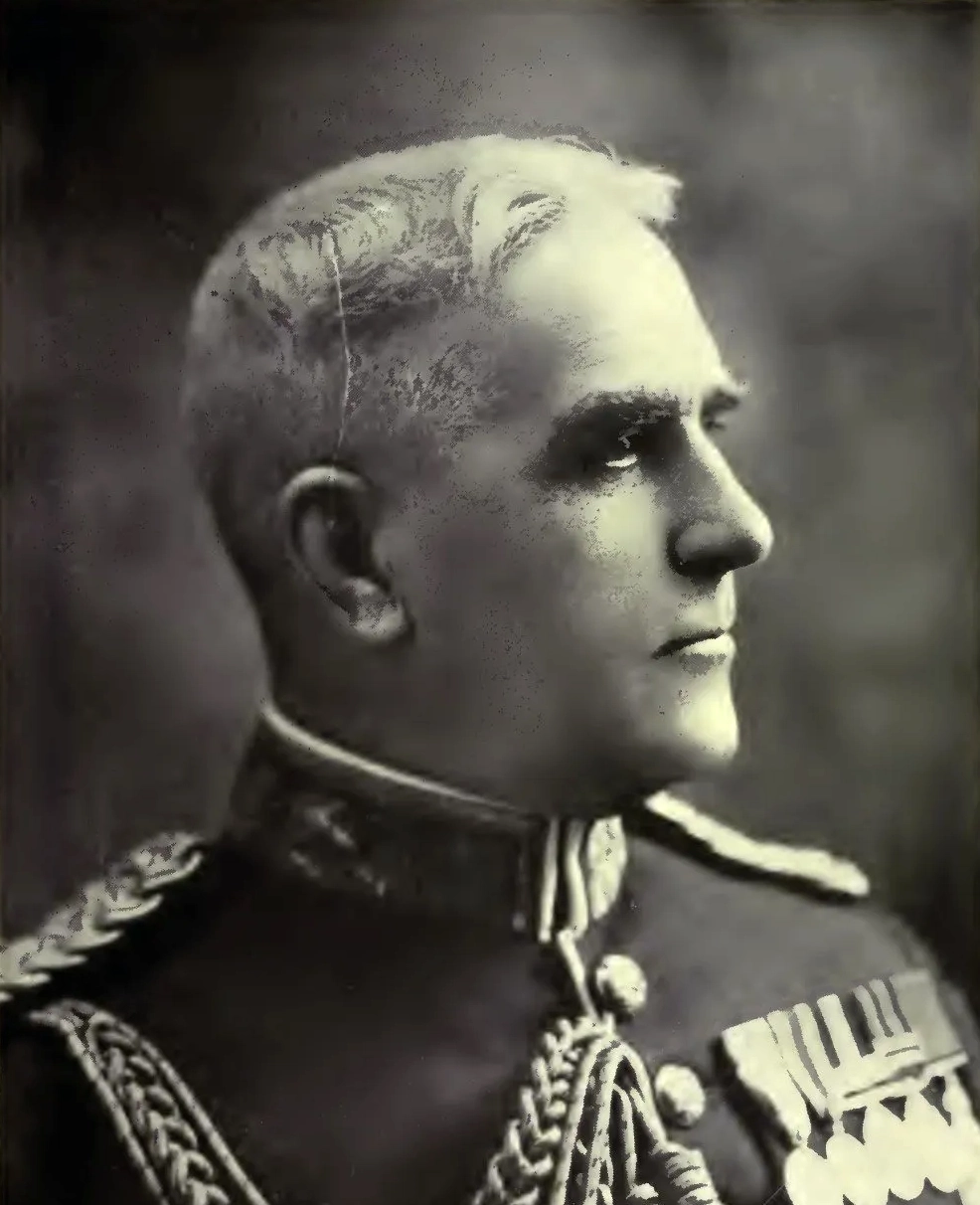

A staunch conservative, an outspoken nationalist, a supporter of Canadian symbols and a strong Canadian army, this part of the world came to know him as the embodiment of patriotism. And as a politician in another troubled time in Canada’s history, just before the Great War, MP Sam Hughes stated:

“Canada must ensure peace with national preparedness for war.”

Hughes put his money and his feisty attitude where his mouth was. Elected member of Parliament for Victoria North riding in 1892, he led Canadian volunteers – citizen soldiers from the Canadian militia – in the South-African war. Though not customary, he insisted on wearing his military uniform in Parliament.

In 1914, as Minister of Militia and War in the Robert Borden government, Hughes organized the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF) for overseas service. In two years, Hughes raised in total about half a million volunteers in the CEF. And he travelled overseas to assist in its training and deployment.

I know this for a fact, because I was recently given his travelling trunk. Coincidentally, our daughter helped some local residents downsize their farmhouse for a move. Among items they passed on was a metal suitcase (four feet long, three feet wide, and four inches deep) with a shipping label and a brass plaque on its exterior: “Col. The Honourable Samuel Hughes, M.P.”

This is the case in which Sam Hughes packed several of those treasured uniforms. It was Sir Sam (knighted in 1915) who influenced the lives of many young men in this region of Ontario; he renamed the Ontario County Battalion, the 116th for convenience. How his metal suitcase came to be in our community I still don’t know; but I hope it will shortly join the artifact collection at the Uxbridge Historical Centre.

Oddly, that’s not the only box of military memorabilia I’ve encountered.

About 10 years ago, I met a retired banker and collector named Frank Moore; he arrived at my Centennial College office and set a small brown suitcase on the table in front of me. It was full of letters that had all been sent to a woman named Catherine McCracken, who’d lived in Montreal during the Second World War. Her son, Alex McCracken, 21, had enlisted in the RCAF, become a navigator aboard a Halifax bomber, and was shot down with six other crewmen on July 25, 1943.

The first of the letters to Mrs. McCracken had come from the commanding officer of the Pathfinder squadron in which her son had served.

“It is the sincere wish,” C.O. Johnny Fauquier wrote her, “that your son will be found safe.” That letter was followed by another a few days later (in the suitcase as well) from the RCAF casualties officer at National Defence. In it he provided Catherine McCracken with the names of the next of kin of all her son’s crewmates: the parents of Cliff Kettley, 23, (wireless radio operator) in British Columbia; the parents of Mickey Tomczak, 23, (pilot) in Saskatoon; the parents of Ed White, 21, (air gunner) and Alex Sochowski, 22, (bomb-aimer), both from Saskatchewan.

Suddenly confronted with the names of all the other families, as much left in the dark about their sons’ fate as Catherine McCracken was, she began to correspond with the other mothers of the missing airmen. The first evidence of that contact arrived in the mail at the McCrackens’ Montreal home in November 1943. Rosalie Kettley, parents of Cliff, wrote a thank-you note to Catherine’s letter of condolence. Mrs. Kettley promised to stay in touch. Finally, she quoted her lost son.

“The last our boy mentioned was his plane,” Rosalie wrote Catherine. “It was ‘LQ-M for Mother,’ as our mothers took good care of us when we were young, we hope our aircraft will continue to do so.”

The only survivor of the air battle that night of July 25, 1943, it turned out, was Alex Sochowski, who bailed out safely. German soldiers took him away to the officers’ prison camp, Stalag Luft III, in Silesia. As the mothers of the downed airmen of bomber LQ-M for Mother would soon learn, the remaining six had died in a fiery crash that night.

But the ultimate loss of their sons didn’t end the correspondence among the mothers. They continued to write of the home-front tribulations of the war, a perspective that historians often overlook.

This week I learned that Frank Moore, who’d saved the suitcase and travelled to Ten Boer, in the Netherlands, where the town paid tribute to the lost airmen, was awarded the King Charles III medal for preserving history.

Such goodness comes from inside unassuming boxes.