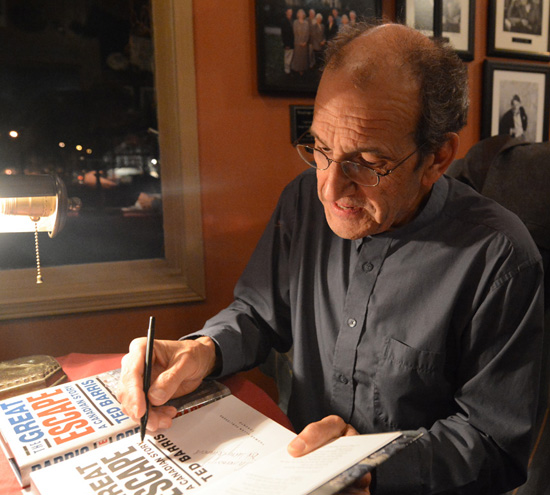

Over the weekend, my wife and I arrived at our daughter’s and son-in-law’s house. As usual, we brought the coffee and donuts. Our grandchildren supplied the entertainment. Last Saturday, Wyatt (who’s nearly two) and I played a little floor hockey in the kitchen. I flipped a rubber ball his way. He chased it – arms and stick flailing every which way – and then he whacked the ball back to me. It wasn’t too long before I cautioned him out loud.

“Be careful,” I said. And then almost instinctively, I added, “I don’t want you knocking somebody’s eye out.”

It wasn’t a really serious warning. In fact, he’s not old enough to understand many of the words in the warning. And, in truth, the only damage he might have inflicted would have been chipping a bit of plaster from a wall or denting a baseboard or two. My blurting out the warning was just a grandparent being protective and playing it safe.

But isn’t that a telltale sign of the times? We’re always telling our kids to take care, watch out and be safe. Funny, I don’t remember my parents ever saying that to my sister and me when we were growing up. In fact, like most parents back in the 1950s and ’60s, our folks pretty much kicked us out of the house most early evenings and weekends just to get us out of their hair.

As long as we came back for suppertime or bedtime, I don’t think our parents ever worried where we went, because we were often in the company of the rest of the kids on the block. I don’t imagine they cared what we did, because we generally played in the backyard of one set of parents or another. And nobody worried just when we got home, since somebody along the block would call one of the kids inside and that would usually break up the playmaking for another day. Safety never really became an issue, unless somebody got more than a bruised knee or a cut lip. Those were just flesh wounds and to most families that seemed par for the course.

As long as we came back for suppertime or bedtime, I don’t think our parents ever worried where we went, because we were often in the company of the rest of the kids on the block. I don’t imagine they cared what we did, because we generally played in the backyard of one set of parents or another. And nobody worried just when we got home, since somebody along the block would call one of the kids inside and that would usually break up the playmaking for another day. Safety never really became an issue, unless somebody got more than a bruised knee or a cut lip. Those were just flesh wounds and to most families that seemed par for the course.

The other thought I had when I warned my grandson about his flailing stick was that scene in the movie “A Christmas Story.” That’s when the character Ralphie says, “I want an official Red Ryder air rifle.” To which one of his parents says, “No way. You’ll shoot your eye out!” And I guess that was the genesis of the paranoiac parent, who fussed and worried over everything his/her children explored for fear it could kill him. (Frankly, I’d have used the “shoot your eye out” line just to keep my kids away from any real firearms or even toy guns, but that’s a different discussion.)

In the 1970s and ’80s, as parents of young children, my wife and I were very conscious of the need for safe playgrounds and even safer streets. I remember “street-proofing” our kids not to talk the strangers and on occasion volunteering to stand around teeter-totters and swings just to make sure nobody got hurt to make the school liable for damages. It was the beginning of the era when municipalities, school boards and parents suddenly felt kids had to be protected from everything.

But wasn’t it our moms who told us, “You have to eat a peck of dirt before you die”?

And we often did eat dirt in pursuit of being king of the castle. I remember with both horror and gratefulness one occasion when a bunch of us kids went off into the woods to climb the tallest and most accessible of the trees – the cedars. My sister had absolutely no fear of heights. I was just the opposite. She scampered up the oldest, driest cedar tree, while I just hung upside down from the lowest, thickest branches.

Then it happened. I heard a crack above me and my sister came crashing down breaking through every cedar branch en route to the ground; in retrospect I guess the cedar limbs probably saved her. On the ground, she was screaming in pain, but she was very conscious. No matter. I was off like shot to retrieve the doctor who lived next door. And he was back just as rapidly, only to find my sister cut and sore, but with all the climbing kids gathered around her laughing about the commotion she’d caused.

There was something about play 50 years ago. Rightly or wrongly, we never considered the danger – either real or imagined. We all looked out for each other. And we never worried because our parents never appeared to worry. Today, I guess everything’s reversed. We teach our kids (or their kids) to worry because we worry, whether danger lurks or not. We want everybody to be safe from all risk at all cost.

In so doing, we may have taken away our kids’ best defence mechanism – lack of fear.