We arrived before the city was awake. The sun had just slipped above the eastern entrance to the lagoons of Venice, where our cruise ship was met by a speedboat bringing the required harbour pilot to guide us into port. Minutes later, we passed some of the historic sites of the city – the Grand Canal, St. Mark’s Basilica and the Doge’s Palace. Someone beside me on deck noticed how few people there seemed to be walking along the canals or through the campos (squares).

“Seems so peaceful and untouched,” he said.

“The really big cruise ships haven’t arrived yet,” another traveller commented sarcastically.

He was right. Our ship, M/V Aegean Odyssey with a modest complement of perhaps 300 passengers, hadn’t been moored at the Marittima Pier at the western edge of the city more than a couple of hours, when suddenly it became surrounded by a fleet of recently arrived cruise ships – Silver Wind, Celebrity Sihouette and Sovereign Pullmantur, to name a few. With lengths as great as that of Titanic and a passenger capacity of 4,000-plus, these floating hotels at first seemed the lifeblood of the city’s vital tourism industry. But according to a lecturer aboard Aegean Odyssey, the large ships may ultimately be contributing to Venice’s demise.

“Venice is now attracting as many as 30 million tourists a year,” said Gregory Dowling, a professor at the University of Venice. “The city has the highest tourist-to-resident ratio in Europe.”

Why is that such a bad thing in a Europe struggling to right itself after the economic crash of 2008? Well, among other things, the rising tourism in Venice, Dowling pointed out, has overwhelmed services (including such basics as public toilets), closed schools and driven residents from the city.

In 1951 Venice was home to 175,000 permanent citizens; in 2012, that number had shrunk to 58,000. That’s not to say that the trend has gone unnoticed; last year, local demonstrators swam in the canals and marched on city squares protesting cruise ships using the historic Giudecca Canal as a highway. The city responded in January, reducing by 20 per cent the number of ships weighing more than 40,000 tonnes.

But the invasion of Venetian canals by so-called “skyscrapers of the sea” is not the only assault on Europe’s antiquities.

Earlier during our recent tour to the eastern Mediterranean, we visited the Acropolis. The iconic mountain top above Athens has stood since the 5th century BC as a symbol of Greece’s “golden age” of enlightenment, democracy and architecture. But it too has suffered from centuries of popularity. As recently as when I was a teenager, in the 1960s, my parents took my sister and me to visit relatives in Athens, where my dad’s cousin led us throughout the Acropolis; back then, we were allowed to wander among the ruins of the Temple of Athena, the Porch of Caryatids and every metre of the Parthenon itself. Not today.

“We are restricted to stay within the fenced pathway,” our Athenian guide told us on our recent visit. “They are very serious about this.”

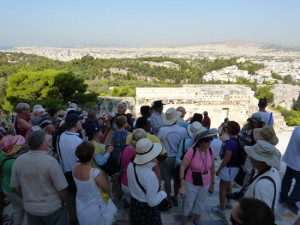

Indeed, when I ventured to the top of an ancient stone piece to photograph our group (seen here), one of the volunteer guardians of the Acropolis blew a whistle at me shouting at me to get down. As I walked the marble pathway, which I remember being jagged and coarse in 1964, I realized the surface is now worn so smooth as to nearly shine in the Athenian sun. And all around the ancient Grecian ruins are cranes and artisans working to repair and restore some of the Acropolis’s former glory.

“The Parthenon took six years to build [in 5th C BC],” our guide informed us. “Restoration has been going on for 80 years; there are still 40 more years to go before it’s complete.”

The restorers of Europe’s antiquities are serious in every respect. As well as restricting movement among the ruins, in most basilicas, churches and mausoleums we explored recently, there were prohibitive signs posted everywhere. Visitors cannot touch, lean on or photograph with flash any of the religious icons and frescos. Clearly the free-access attitudes of the past are gone. Exhibitors, guides and museum curators all fear the damaging potential effects of their attractions’ popularity.

As far as preserving the Venetian canals, I noticed the day after we left the city once dominated only by gondolas, that Italy’s transport minister has clamped down even more.

After civic petitions and celebrity press conferences (involving Michael Douglas and Cate Blanchett), Maurizio Lupi, announced further restrictions on the mega cruise ship invasion. Soon, no ocean liners over 96,000 tonnes will be allowed to sail the Giudecca Canal in front of St. Mark’s Basilica.

“[It’s] our duty to remove the skyscrapers of the sea from the canals of Venice,” he said, “safeguarding a world heritage city … [while] protecting the city’s economy so linked to cruise tourism.”

But is it a case of fiddling while Rome burns?