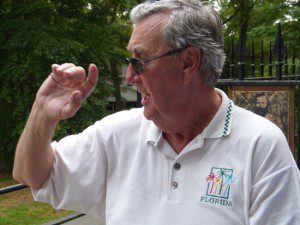

Travellers whiz along this stretch of the U.S. interstate highway in central Virginia without blinking an eye. Most are driving the few miles on I-95 to shop or dine in Richmond, Virginia, or are commuting the short hour to work in Washington, D.C. Only history buffs realize that near this turnoff, just north of the former capital of the Confederate States of America, stands a monument marking a critical moment in the American Civil War. Paul Van Nest, a Civil War guide from Kingston, Ont., never passes this spot without stopping to remember events here.

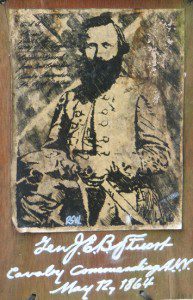

“At this spot,” he described to my tour group this week, “a Federal soldier sees no less than Confederate commander J.E.B. Stuart, aims his revolver and fires a deadly shot that passes right through Stuart’s body.”

The day Stuart died, May 12, 1864, the war between the Union and the Confederacy had raged for more than three years. It would go on for another year, cost a recently revised estimate of 750,000 soldiers’ and civilians’ lives, and take the life of President Abraham Lincoln.

In addition, for guide Paul Van Nest, now 75, Gen. Stuart’s passing was a bleak turning point in the life of the Confederacy. In just a matter of months, he pointed out, Southern commander Robert E. Lee had endured repeated military setbacks in his home state of Virginia and lost upwards of 20,000 casualties, nearly a third of his army. Perhaps most devastating, as tour guide Van Nest saw it, Gen. Lee had sustained a personal loss here.

“Lee felt very close to J.E.B. Stuart,” he said. “Losing him was like losing a son.”

Historian Paul Van Nest, who has led no fewer than 55 different Civil War tours in some 27 years, doesn’t gloss over the equally catastrophic aspects of the U.S. war of secession – state versus federal rights, plantation economy versus industrial economy, and slave versus non-slave proponents. To be sure, discussion among those travelling on this tour has been continuous, constructive and occasionally contentious.

Like so much else in our neighbouring cultures, whenever Americans have experienced upheaval, Canadians have always paid attention. One member of our group even picked up a book entitled “The South Was Right!” by Ronald and Donald Kennedy, who claim most Civil War history is untrue because it was written by the victors. I tend to endorse the sentiment in “Fields of Honor,” a book I picked up by Edwin Bearss, historian emeritus with the U.S. National Park Service.

“The enduring interest in America’s Civil War,” Bearss wrote, “comes from the direct connection many people feel with the people who fought in it.”

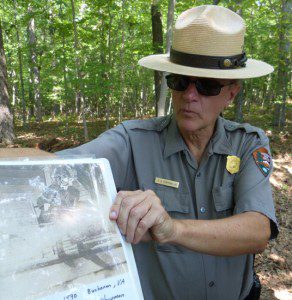

That’s likely one of the reasons why Richard Chapman Jr., a National Park Service historian, has invested a decade of his life in storytelling around events of the Civil War. His great grandfather James Chapman fought with the 42nd Virginia Volunteer Infantry at such landmark battlefields as Manassas, Fredericksburg and Gettysburg. We met Chapman Jr. at a place called Saunders’ Field, where on May 5, 1864, his ancestor had assisted in repulsing a Federal Army attack during what was known as the Battle of the Wilderness. Walking us across what had been a bramble-choked cornfield 150 years ago, Chapman described the slaughter of Union troops as witnessed by attacking Col. George Ryan of a New York regiment.

“I saw my men melt away like snow,” said Chapman quoting Ryan. “Men disappeared as if the earth had swallowed them.”

Chapman, now 62, remembered learning Civil War history as a kid. He even admitted, in a childhood fantasy, writing in his notebook, “the next president of the Confederacy, Richard Chapman Jr.” He went on to earn his master’s degree in history at the University of North Carolina and another degree in communications at James Madison University. He’d even served in the U.S. Army in Germany in the 1970s. But he said merely being a Virginian and knowing all this history had happened in his backyard drew him to telling war history for a living. And Chapman didn’t mind offering his own what-if scenario of Saunders’ Field.

“Had the Confederates’ counter-attack not been halted by darkness,” Chapman mused, “that famous quote by [Gen. Ulysses S.] Grant, ‘Some of you think that Lee is all of sudden going to do a somersault and land in our rear on both flanks,’ might actually have come true.”

In America, whether Blue or Grey, they explore, expound and extrapolate their past. Paul Van Nest, our Canadian tour leader, made sure we understood that as we explored the battlefields of southern Virginia. He also shared the burden that all war historians carry. As he stood beside the stone monument that memorialized J.E.B. Stuart’s death at the Battle of Yellow Tavern, tears welled up.

“I feel for both sides,” he said. “Because this story was repeated over and over again. Sometimes, all you can say is, ‘Why?’”