The day seemed rushed and complicated. People and vehicles rushed in every direction. Time flew more quickly than anyone wanted. There seemed no room, but to hurry through the day. It was D-Day, 2014, and we had tried desperately to get to an appointment with history – a commemorative ceremony at Bavent, in Normandy, France. In fact, when we arrived, the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion padre, who had already conducted the scheduled ceremony, realized our predicament.

“I know you weren’t late 70 years ago,” he said. “However, traffic jams and road blocks notwithstanding, you’ve made it.”

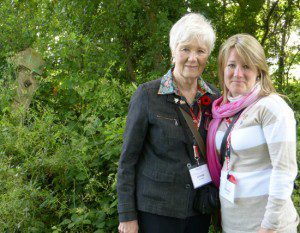

Two veteran members of the original Canadian Paras – Mervin Jones, 91, from Quebec, and Robert Sullivan, 91, originally from Oregon – and Joanne de Vries representing her late husband, paratrooper and Legion of Honour recipient Jan de Vries of Toronto, had rushed in to the Bavent memorial location at the last moment.

“And it would be a shame not to mark this occasion with your comrades and your successors today,” the padre noted.

And so, the young clergyman conducted a second, smaller commemoration to fallen members of the battalion. On that very day – June 5 – 70 years before, Jones, Sullivan and Jan de Vries had parachuted from transport aircraft into the night to protect the flanks of the invasion beaches – Utah, Omaha, Gold, Juno and Sword – not knowing if they might succeed or die in an attempt to dislodge the Nazis from occupied Europe.

On this 70th anniversary of the Allied invasion, I and 48 other Canadians (who had travelled to France for D-Day commemorations and were also late for the original tribute) were relieved that Joanne de Vries would be allowed to join the veteran Paras placing a wreath of poppies at the foot of their regiment’s Bavent memorial.

“They were young,” the padre said before the minute’s silence. “Strong of limb, true of eye. Staunch to the end against odds uncounted.”

By the middle of the D-Day morning, June 6, 1944, about the time 150,000 assault troops were establishing the Normandy beachhead behind them, survivors of the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion had achieved all the objectives assigned them in Operation Overlord. They had captured a vital German battery, made impassable all the bridges on the eastern flank of the D-Day landings, and they had isolated potential German counter-attacks.

“In fact, Jan had landed miles from his intended objective,” Joanne de Vries told us this week in France. Then, following the wreath-laying ceremony at the Paras’ memorial, she walked us up the road to where her husband, Jan, had dug a slit trench on the evening of June 6, 1944, and defended this spot unrelieved for almost two months.

I have always admired Joanne de Vries’ support for her husband’s post-war campaign raising the profile of veterans. When Jan de Vries co-founded the Juno Beach Centre in Courseulles-sur-Mer, when he led the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion Association, and when he spearheaded the effort to keep fellow Para Fred Topham’s VC medal in Canada, Joanne de Vries was there at his side. Now she does it in his memory.

A few kilometres away from the Canadian Paras’ site at Bavent, another of the women who joined the 70th anniversary D-Day commemorative tour I’m hosting this year, paid tribute to her father’s Normandy campaign story. On June 6, last Friday morning, we visited Beny-sur-Mer, home of Canada’s D-Day cemetery.

Pat Rusciolelli checked the Commonwealth War Graves Commission site directory and then walked to the grave of trooper K.G. Starfield. She stood at behind his marker and explained to me what had happened. In early July, Starfield and Pat’s father, T.A. Bullock, were travelling in a Bren-gun carrier. At that time, their regiment, the 14th Canadian Hussars, was supporting the Allied liberation of Caen in an area known as Louvigny. A German mortar shell landed in the carrier, and severely wounded both men. Starfield died on July 15. Pat’s father nearly died.

“A piece of shrapnel lodged beside my dad’s spine,” she said. “He was paralyzed. They came to him and asked if he was OK. But the concussion had twisted his legs backwards, so he didn’t think he was.”

Pat went on to explain that her father thought he’d lost both his legs because he couldn’t feel them. Bullock was shipped home to Canada, where he eventually learned to walk again living a relatively normal life. As she stood there expressing how privileged she felt to attend Starfield’s grave at Beny-sur-Mer, Pat Rusciolleli was on the verge of tears. She pointed out her father was alive and well back home in Canada acknowledging an important moment.

“My father is 92 today,” she said. “Happy Birthday, Dad.”

Of course, wreaths and graveside visits – even on coincidental birthdays – don’t keep the memory of veterans alive. It’s the act of revisiting their achievements. If we continue to tell and retell the stories of their service, they live on.