When two recent acquaintances of mine arrived at the former Stalag Luft III location, in September 2013, they expected that the former German prison camp, while now a museum site near the town of Zagan in western Poland, would be fairly peaceful. The two Britons (as well as builder David Dunn and painter Johnnie Tait) had plans to erect a replica sentry tower in time for the upcoming 70th anniversary commemoration of The Great Escape eight months later. Andy Hunter, one of the two tower builders, was suddenly startled by what he saw.

“The day we arrived, we were suddenly confronted by a World War II German military motorcycle and sidecar,” Hunter said. “The occupants were dressed in German military uniform. And they had guns pointed at us.”

Hunter’s heart palpitations, while understandable, were unnecessary. He soon discovered that the entire area around Zagan, including Stalag Luft III (the location of The Great Escape in 1944,) was in overdrive preparing for the commemorative ceremony, scheduled to happen right next to the replica sentry tower. And the men with German uniforms, motorcycle and guns were simply re-enactors also preparing for the 70th anniversary observances. In fact, the curator of the site, the Museum of Allied Forces Prisoners of War Martyrdom, Marek Lazarz, when I caught up with him just before the commemoration on Monday, seemed startled by the momentum.

“We’ve had more visitors here in the past few days,” Lazarz said, “than we’ve had in a year.”

Lazarz and I first met three years ago as I prepared my telling of The Great Escape story with a Canadian perspective. Even then, the tall and lean director of the museum explained that he prayed everything would be ready for the anniversary – the new exhibits hall, the souvenir sales area, the replica of Hut 104 (from which the famous Great Escape tunnel “Harry” was excavated to deliver 80 Commonwealth air officers outside the wire on March 24/25, 1944), the ceremony site near the exit shaft of tunnel “Harry,” the military personnel, the ambassadorial dignitaries, any surviving POW vets, and the re-enactors.

In fact, when I caught up with Lazarz on Sunday afternoon he was dressed in an RAF officer’s uniform as part of the re-enacting team himself. At that moment, he’d found Stalag Luft III POW veteran Andy Wiseman, who’d come in from the U.K. for the commemoration. Lazarz was escorting the 90-year-old Stalag Luft III alumnus to a mock inspection.

“The Germans conducted a roll call twice a day,” Wiseman told me. He further explained that the Luftwaffe guards in the camp counted each row of POWs calling out the total from front to back to front. Whenever they could the Canadian, British, New Zealand, Australian and South African air officer inmates moved around in mid-count.

“We did our level best to mess things up for them,” Wiseman said. “It was our job to confuse the enemy as often as we could.”

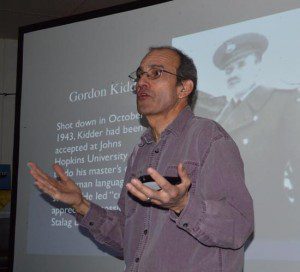

Later that Sunday evening, my fellow travellers to Stalag Luft III – Mark Christoff from Uxbridge and Gord Kidder (whose uncle RCAF navigator Gordon Kidder escaped through the tunnel, but was later killed) – attended a reception hosted by the Canadian ambassador to Poland. Besides the requisite diplomats, civic officials and military dignitaries, Ambassador Alexandra Bugailiskis acknowledged another important volunteer component in the anniversary.

“I remember seeing the Great Escape movie as a little girl,” she said. “But I had no idea the extent to which the POWs families contributed to their survival of Stalag Luft III.”

Among her invited guests, brother and sister Keith and Jean Ogilvie were representing their father Keith (who was recaptured, but survived); Peter McGill and son Adam attended in remembrance of Peter’s grandfather, George McGill (murdered by Gestapo); and Gord Kidder was honouring his namesake, Gordon Kidder (killed by Gestapo after the escape).

“We often forget the impact of these events on their families,” Ambassador Bugailiskis said. “And yet the families’ connection to these POWs likely gave them hope to get through their days as POWs.”

Andy Hunter, with the British Ministry of Defence, and British Army Col. Phil Westwood, his team leader in the construction of the replica sentry tower at Stalag Luft III, represented another blood connection to events this week near Zagan. Westwood served 38 years in the British Army with deployments to Iraq, Afghanistan, Falkland Islands and Northern Ireland, he told me.

“We built the replica of Hut 104 (with the trapdoor to Tunnel “Harry” under a stove,)” Westwood said, “and with some of the donations leftover, we came up with the idea of building the sentry tower… It just seemed the right thing to do.”

Monday’s commemoration at Stalag Luft III and tribute to the 50 murdered Commonwealth officers succeeded because the re-enactments and artifacts were frighteningly believable… but more because volunteers involved knew a legacy was at stake and felt moved to contribute.