As a Newfoundlander, she pointed out that back home there are two important observances on July 1.

As a Newfoundlander, she pointed out that back home there are two important observances on July 1.

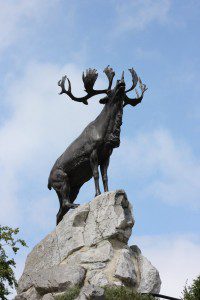

Each year when the first day of July dawns, Shandel Leamon explained, Newfoundlanders mourn the events at Beaumont-Hamel, France, in 1916. On that July 1, as the Somme offensive began during the Great War, British generals sent hundreds of thousands of Empire soldiers over the top against an occupying German Army. In less than half an hour nearly the entire 1st Newfoundland Regiment – 658 men – became casualties.

“A span of two football fields,” Shandel Leamon explained, “took two months to take from the Germans.”

But then in the evening each July 1, the young student from Little Rapids, Newfoundland, pointed out that she and her fellow citizens celebrate joining Confederation. The island dominion formally became the 10th province of Canada on July 1, 1949. The evening therefore turns into a celebration with promenades, parties and, of course, fireworks.

I met Shandel Leamon and her co-workers – all Canadian university students in the employ of Veterans Affairs Canada – earning tuition money this summer at the Beaumont-Hamel historic site in France.

I had come 6,000 kilometres from Canada and met some of the proudest Canadians I’ll find anywhere. Wearing the VAC uniforms and full of stats, stories and history, they seemed devoted to their work.

(more…)

Earlier this week, I happened to be on a massage table. Because my massage therapist also happens to be one of the most plugged-in and erudite people I know, she and I talked about the devastation in Haiti. To my surprise, she informed me that Uxbridge has become involved. She said that among a number of awareness-raising and fund-raising activities, the Rotary Club of Uxbridge has rallied to assist victims of last Tuesday’s earthquake. I wondered how our community – so far away from the disaster – could hope to deliver any tangible help.

Earlier this week, I happened to be on a massage table. Because my massage therapist also happens to be one of the most plugged-in and erudite people I know, she and I talked about the devastation in Haiti. To my surprise, she informed me that Uxbridge has become involved. She said that among a number of awareness-raising and fund-raising activities, the Rotary Club of Uxbridge has rallied to assist victims of last Tuesday’s earthquake. I wondered how our community – so far away from the disaster – could hope to deliver any tangible help. It happened early last spring. With just a few days remaining before I led one of my annual tours to the battlefields of Europe, I paid a visit to the man who regularly supplies me with this country’s greatest calling card.

It happened early last spring. With just a few days remaining before I led one of my annual tours to the battlefields of Europe, I paid a visit to the man who regularly supplies me with this country’s greatest calling card.

As a Newfoundlander, she pointed out that back home there are two important observances on July 1.

As a Newfoundlander, she pointed out that back home there are two important observances on July 1.