It’s a repeating theme in much of his published work, but this week perhaps more than most, Ted Barris’s focus on unheralded Canadian heroism during the Second World War appears to have some resonance.

It’s a repeating theme in much of his published work, but this week perhaps more than most, Ted Barris’s focus on unheralded Canadian heroism during the Second World War appears to have some resonance.

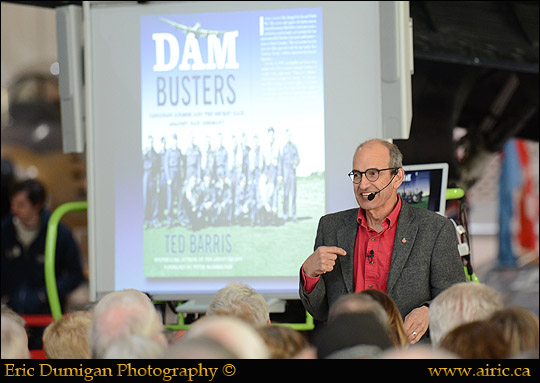

In recognition of the 75th anniversary of the famous bombing raid against the Ruhr River valley war munitions factories of the Third Reich, Ted Barris offered his first ever talk/presentation on the story of the famous “Dam Busters” raid at the Canadian Warplane Heritage Museum in Hamilton.

About 500 museum members, history buffs, some veterans and the general public filled seats in front of the museum’s WWII Lancaster inside the main hangar to hear the talk. Barris borrowed a comment from one of the Royal Air Force officers featured in the 1955 movie The Dam Busters who told Guy Gibson, the wing commander of No. 617 Squadron, “We mustn’t forget the English” when hand-picking airmen for the raid.

About 500 museum members, history buffs, some veterans and the general public filled seats in front of the museum’s WWII Lancaster inside the main hangar to hear the talk. Barris borrowed a comment from one of the Royal Air Force officers featured in the 1955 movie The Dam Busters who told Guy Gibson, the wing commander of No. 617 Squadron, “We mustn’t forget the English” when hand-picking airmen for the raid.

“We mustn’t forget the Canadians,!” Barris emphasized in response.

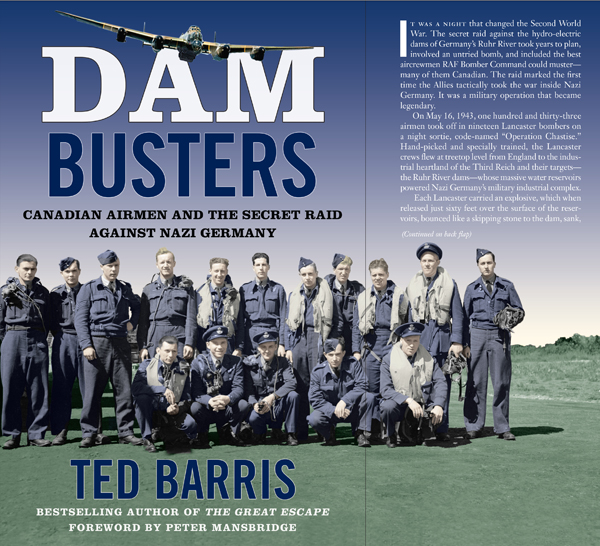

During the 50-minute presentation, Barris drew on research, interviews and narrative featured in his forthcoming book, Dam Busters: Canadian Airmen and the Secret Raid against Nazi Germany, to be published by HarperCollins this year. The raid on May 16-17, 1943 required 19 specially modified Lancaster bombers to travel at treetop altitude – less than 100 feet off the ground and the water – from Scampton air base in Britain to the Ruhr Valley in the heart of Germany to attempt to destroy the Möhne, Eder and Sorpe dams. They breached the first two and damaged the third, but in the course of the combat operation lost eight bombers including 56 airmen.

During the 50-minute presentation, Barris drew on research, interviews and narrative featured in his forthcoming book, Dam Busters: Canadian Airmen and the Secret Raid against Nazi Germany, to be published by HarperCollins this year. The raid on May 16-17, 1943 required 19 specially modified Lancaster bombers to travel at treetop altitude – less than 100 feet off the ground and the water – from Scampton air base in Britain to the Ruhr Valley in the heart of Germany to attempt to destroy the Möhne, Eder and Sorpe dams. They breached the first two and damaged the third, but in the course of the combat operation lost eight bombers including 56 airmen.

Barris pointed out that of the 133 airmen specially chosen and trained in seven and a half weeks prior to the raid, nearly a quarter of those were Canadians. Thirty aircrew – pilots, navigators, flight engineers, wireless radio operators, bomb aimers and gunners – came from nearly every province in the country. What made the story equally important as a Canadian story, Barris pointed out, was that nearly half those chosen for the raid received their training in the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan operated principally in Canada between 1939 and 1945.

Barris pointed out that of the 133 airmen specially chosen and trained in seven and a half weeks prior to the raid, nearly a quarter of those were Canadians. Thirty aircrew – pilots, navigators, flight engineers, wireless radio operators, bomb aimers and gunners – came from nearly every province in the country. What made the story equally important as a Canadian story, Barris pointed out, was that nearly half those chosen for the raid received their training in the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan operated principally in Canada between 1939 and 1945.

“The elephant in the room is that almost half the Dam Busters received their air training in Canada,” Barris said, “and that’s not been recognized before.”

“The elephant in the room is that almost half the Dam Busters received their air training in Canada,” Barris said, “and that’s not been recognized before.”

The Canadian Warplane Heritage Museum, who staged the presentation, houses among the largest collections of air-worthy wartime aircraft, including the Mynarski Memorial Lancaster, which towered over Barris and the audience during the presentation.

Dam Busters: Canadian Airmen and the Secret Raid against Nazi Germany is due for release in September, as a Patrick Crean Edition book from HarperCollins Canada.

(Photographs courtesy Eric Dumigan Photography – more images at: http://www.airic.ca/html/2018cwhdbraid.html)