In his time, the man reported on the Mau Mau uprising in Africa, race riots in the southern U.S., and a near nuclear war over the Cuban missile crisis. He interviewed popes, presidents and just plain people. In the middle of times of upheaval and change – the 1960s – he met and reported on Che Guevara, James Meredith, Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech.

Finally, in 1978, he won the battle for the most coveted seat in broadcasting – the host’s chair at “The National” at CBC TV – and stayed there a decade. But Knowlton Nash was perhaps most drawn to reporting on a war in his very own backyard.

“Nowhere in the world has the battle over the kind of broadcasting we hear and see been fought with more ferocity than in Canada,” he told one my journalism classes in October 2001.

I have been proud to use as textbooks some of Knowlton Nash’s published writings about broadcasting, including “The Microphone Wars: A History of Triumph and Betrayal at the CBC” and “The Swashbucklers: The Story of Canada’s Battling Broadcasters.” Indeed, in 2001 he addressed my students at Centennial College about his research and writing of history versus his work on air.

“Writing books about broadcasting,” he told us, “is more challenging, more demanding (but) more satisfying.”

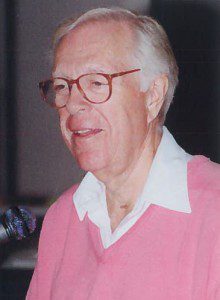

Knowlton Nash started writing his own newspaper at age 10, sold stories about collegiate football to the Globe and Mail as a teenager, thrived as a Washington correspondent, and then shaped the flagship nightly newscast at CBC TV through one of its most critical times – the 1980s. Under his guidance as anchor and senior correspondent, Nash helped to move the broadcast from 11 to 10 p.m. each night. And in so doing, he earned the trust and adoration of the Canadian public; often his viewers referred to Nash as “Uncle Knowlty.” Then, in retirement he turned to documenting Canada’s broadcasting roots – the birth of both private and public radio. He had completed nearly a dozen books when he died of complications from Parkinson’s disease last weekend at age 86.

As a fellow broadcaster I watched his more than smooth delivery from behind those over-sized glasses each night at 10. I admired his command of the historical context of the times, seeming to have at his fingertips every milestone relevant to the day’s news. I applauded his calm demeanor, though all the world seemed half-crazed and running in circles.

I think Knowlton Nash’s even greater contribution to the airwaves came after his celebrity on The National, when he wrote about the earliest days of broadcasting, when he said for example, “radio became the poor man’s theatre… a God-send during the Depression.” In his book about the CBC, he worshipped the two co-founders of the Canadian Radio League – Alan Plaunt and Graham Spry – attempting to move the Depression-era governments of Mackenzie King and R. B. Bennett to create a public broadcasting network, while the private-enterprise radio station owners of the Canadian Association of Broadcasters lobbied to prevent it.

“The idealists (Plaunt and Spry) wanted to use the airwaves primarily to educate and … strengthen Canadian unity,” Nash explained to my students, “while the Swashbucklers (private radio interests) wanted primarily to provide entertainment that was popular and most of all profitable.”

Knowlton captured the essence of those cut-throat battles both on and off the air. He showed us how the CAB called public broadcasting “international conspiracy… communistic and promoted by intellectual snobs.” But equally critical of the public interests, he showed that they plotted to “strong-arm the federal government” into establishing a public radio system in Canada. Typical of Knowlton Nash’s sense of balance and fairness in the telling of a story, he said, “I hasten to say that the Swashbucklers were not all avaricious philistines … nor were the idealists all ivory tower dreamers.”

In the end of his analysis of the birth of broadcasting in Canada, Knowlton Nash recognized – like so much else in this country – there had to be a great Canadian compromise. He said that Canadian broadcast pioneers forced a “demassification” of media in Canada and “a tornado of change” that allowed a blend of both private and public cultures in order for Canada’s listeners’ needs to be met.

After Knowlton Nash delivered his broadcast history talk to my students, back in 2001, I asked him privately if he’d have preferred to broadcast in those pioneer years. He smiled at the notion, but then recognized that his career had been the best any broadcaster could ask for. Just what you’d expect a trustworthy TV anchor to say.