When he was a kid at school, he dreaded show-and-tell days more than just about anything. Especially around Remembrance Day. When it came time to tell the class what his dad did in the war, sometimes he’d invent a fighter pilot dad. Other times, a bomber pilot dad. But just last week when he reconsidered his father’s wartime career, Rick Askew’s attitude about his dad had changed.

“I had him winning the war all by himself,” he told me. “In truth, he never fired a gun once in the war.”

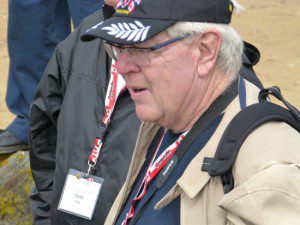

Last week, Rick Askew, a semi-retired cosmetics salesman from Oshawa, travelled with me (and a larger Merit Travel group) in northwestern France. We toured key locations in Normandy where Allied armies had gained a critical toehold against the Nazi occupation of Europe beginning on June 6, 1944. I took him and the tour group to Juno Beach, Pegasus Bridge, Omaha Beach, Pointe du Hoc, where the men of our fathers’ generation had turned the tide of the Second World War. But unlike the history books, I explained to Askew and my other travel guests that it wasn’t the generals and politicians who’d achieved these objectives. It was the average citizen soldiers, such as his father and mine.

To emphasize the point, I offered a story I’d been told by friend Braunda Bodger. A dozen years ago, she’d informed me that her father, a stationery worker in Regina before the war, had come ashore in France in the clerical section of Gen. Bernard Montgomery’s 21st Army Group. I was curious about the role a clerk might have played during the Allied advance. And when I spoke to the man himself – Wally Filbrandt – my view of the entire Allied invasion of Normandy turned on a dime.

“There were reinforcement companies, battalions and brigades all ready to jump into action,” Filbrandt told me. “We would simply receive casualty reports and then assign reinforcements where they were needed.”

In other words, he kept the invasion army functioning in fact the way it was supposed to on paper. It was a remarkable turnabout for me as a documentarian of the war. In those minutes spent with Filbrandt, I’d come to realize that sometimes the least visible acts of service were among the most influential contributors to winning the war. Filbrandt’s dispatching the right replacement ultimately meant the difference between victory and defeat.

Like Filbrandt, Bill Askew (Rick’s father) had served King and country not with a gun, but with a behind-the-lines skill. Askew Sr. had played brass instruments in the RCAF band stationed at Goose Bay, Labrador (then technically “overseas” because Newfoundland and Labrador didn’t join Canada until 1949). He and his 30 fellow bandsmen had played for parades, dances and ceremonies; they were the sound foundation to every official event on base.

“I had him winning the war,” Rick Askew said. “It took me 50 years to figure out he was just as much a veteran as anybody.”

Actually, Rick Askew had joined my Normandy trip for a number of reasons. Initially, a few months ago, he’d decided to get his buddies at a club in Oshawa to autograph of Canadian Maple Leaf flag. It would be up to Rick to find the right veteran attending D-Day ceremonies in France to receive the autographed flag as a symbol of gratitude and remembrance. As we awaited the ceremony last week at Juno Beach, Askew suddenly ran up to me.

“I found him,” he told me excitedly.

“Who?” I asked, not remembering his plan.

“The vet to receive our autographed flag.”

He led me through the maze of vets awaiting the 70th anniversary ceremony in front of the Juno Beach Centre and introduced me to Bill Opitz, who’d served as a stoker aboard the Royal Canadian Navy minesweeper HMCS Bayfield on D-Day. Ultimately, that proved only half of Rick Askew’s quest in France. During most mornings, when he smoked a cigarette out on the balcony of our hotel in Normandy, he began to realize the diversity of service that Canadians had delivered that spring back in 1944, had actually included his father.

With the story of Filbrandt in his thoughts and with his autographed flag delivered to an ordinary navy stoker, Rick Askew perhaps sensed his father’s role as a bandsman had been more important than a son had given his father credit. As a bandsman, the elder Askew had given tempo to military parades, melody to receptions and often the correct somber atmosphere to station memorials. He’d learned that service in such a desperate time had come in all shapes, sizes, and contributions.

“This trip has changed my life,” Rick Askew told me on the last day of our tour. “I’m really proud of what my father did now.”

He’ll never be afraid of show and tell again.