It’s always wonderful to be recognized for your work. It’s even better when people spot your work and recognize it as being yours. I mean, everybody knows what an Armani suit is. Or a Picasso painting. Most cinema buffs know what to expect from a Marilyn Monroe movie. Or a coffee at Tim Hortons. There was a time, when I produced radio shows in Saskatchewan, that my broadcasting colleagues might see me working late into the night and comment:

“Oh-oh, Barris is in the studio. I wonder who died?”

The reason was that for the several years I worked behind the scenes on a daily morning Saskatchewan radio program – The Wal ’n’ Den Show. Among many things, Wally Stambuck and Denny Carr had a reputation for being close to show business and its stars. So, if one of those luminaries happened to die suddenly, it was expected that they would be on the air the next day with the most inside information about that star and highlights of the career that had just ended.

That’s where I came in. As soon as we got news of a death, I immediately got on the telephone – at my desk in Saskatoon – to find a relative who would reminisce about the good old days, a fan who had a unique encounter to describe or an associate who could spill the beans about what the star was really like.

I remember, for example, when the bushy-browed, wisecracking leader of the Marx Brothers, Groucho Marx, died at 86 on August 19, 1977, I managed to reach renowned composer Marvin Hamlisch, who had accompanied Groucho on piano during his at Carnegie Hall one-man shows. Then, somehow I found a number, which rang through to Groucho’s home where Erin Flemming, his so-called secretary, answered the phone. She had been responsible for bringing the comedian out of retirement to do those “Evening with Groucho” shows. When we rolled tape in the studio and asked about Groucho’s death, she paused.

“He’s just going to have a nap and rest his eyes,” she said, “for the next several centuries.”

During the couple of years I worked on those overnight obituaries, I pulled together retrospectives on such show business greats as Ethel Waters, Vivian Vance, Freddie Prinze, Peter Finch, Sebastian Cabot and Zero Mostel. I know it seems a little weird, but I really enjoyed those long nights finding people who recounted the stars’ achievements. I also loved pulling together recordings of the performers’ radio, TV and movie and appearances and mixing them with our recorded anecdotes in time for broadcast the next morning.

When Mary Ford, the singing wife of electric guitar pioneer Les Paul, died in Sept. 30, 1977, I managed to find a musicologist who reminded us that Mary also played guitar and that the recordings with her innovative husband were unique in the history of recorded music. Les Paul had recently perfected a method of recording separate tracks of Mary’s voice, so that she could harmonize with herself on the final disc. They used this pioneering technique in the 1950s on such songs as “How High the Moon” and “Bye Bye Blues.”

“Mary was truly ahead of her time,” he said.

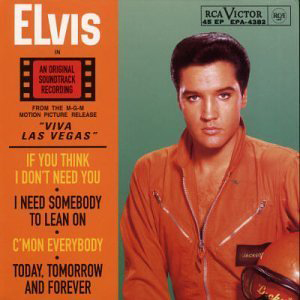

What reminded me the most of my role as radio obituary producer, however, was the night I spent pulling together a documentary on the King of Rock ‘n’ Roll. Elvis Presley died, August 16, 1977, and overnight I had to assemble a cast of interviewees to reflect on the rise of the showbiz legend. By the following morning, I had managed to have Wally and Denny interview Presley’s famous manager – Col. Tom Parker – then, members of Elvis’s backup group from 1956 to 1970, the Jordanaires. They said Elvis gave them the greatest promise of their careers.

“If I ever cut a record,” Elvis told them in 1954, “I want to use you guys singing background.” Their first session together produced a 45-rpm recording with a couple of minor hits – “Hound Dog” and “Don’t Be Cruel.” It remains Presley’s greatest single ever and it made stars of the Jordanaires too.

Finally, the night Elvis Presley died, I found the manager of The International Hotel in Las Vegas, where The King had performed his blockbuster “Viva Las Vegas” show. We learned how huge a star Elvis Presley was in the 1970s. He performed his first show at The International in 1969 and went on to appear in 837 consecutive, sold-out shows to nearly 3 million fans.

“In one month,” the manager said, “ Elvis performed for over 100,000 people and brought in one-and-a-half-million dollars in ticket sales.”

That’s what our audiences learned the morning after Elvis Presley’s death, 34 years ago this week. And even though it was a night of sadness and loss for his fans, for me, I think it was worth staying up all night to discover.