With the potential of even short-lived freedom waiting for them perhaps just days away and at the end of nearly 400 feet of completed shafts and tunnel works, hundreds of kriegies contemplated that potential.

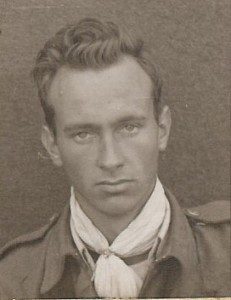

Frank Sorensen, the Canadian Spitfire pilot shot down over North Africa in April 1943, felt the anticipation and excitement as much as any man inside the North Compound of Stalag Luft III. In numerous letters home to his family, Sorensen sometimes exhibited what fellow kriegie Albert Wallace described as a “barbed-wire happy” attitude, that is, an obsession for getting out of prison.

“Indoor life in a kriegie camp,” Sorensen wrote on March 20, 1944, “does not make time go any faster.”

However, several realities in the compound influenced Sorensen’s eventual decision to forfeit his higher position (lower number) on the escape list. X Organization intelligence suggested the first escapers – fluent in German and dressed like businessmen or travellers – stood the best chance of getting away safely if they caught the fast morning trains leaving Sagan. Sorensen deduced those same express trains would also face the greatest scrutiny and surveillance by German police and railway guards. Sorensen therefore considered going through the tunnel lower on the list to catch a later, slower train, where his presence might attract less attention.

But Sorensen weighed yet other considerations. Among his closest friends inside the wire was James Catanach, an Australian officer who’d grown up in a tightly knit family… and Arnold Christensen, a New Zealand officer who shared Sorensen’s Danish heritage. Both Catanach and Christensen had been imprisoned longer than Sorensen had, and in the grand scheme of the mass breakout, their successful escape seemed to hold greater emotional significance, at least in the way Sorensen looked at it.

So, for strategic purposes or matters of the heart – or both – Sorensen chose to trade his earlier spot on the escape list for a higher number and later exit through the tunnel.