It took a little while, but I found out what the overseas area code for the United Kingdom was. Then – this was 1980 – I asked for directory assistance in London. I naively inquired about a residential phone number. To my astonishment, they had his number. I carefully composed myself, dialled, and fully expected either an assistant or someone running interference to answer. The phone rang a few times. Then, a man answered.

“Hello,” the voice said in an Oxfordian accent.

“Hello,” I said, not believing someone had actually picked up the phone. “Ah, would Dr. Bannister be there?”

“Speaking…”

I remember seeing the grainy black-and-white film in my history class, when I was 14. But it had just as much resonance as if I had seen it in my phys-ed class. There was this tall, string-bean of a runner striding those last few yards. Gasping for air, in his runner’s shorts and striped jersey, he plunged through the tape, while sporting officials and spectators closed in around him, trying to blend into his extraordinary-ness. He had done it.

“Three minutes, 59.4 seconds. Shattering the four-minute mile, the Everest of athletic achievement,” the voiceover announcer on the newsreel said. “Well done, Roger Bannister!”

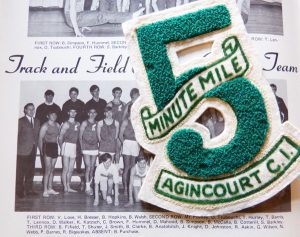

And as a novice long-distance runner, I was inspired. I remember donning my runner’s tank top later that day in 1963. And tying my running-shoe laces with extra vigour. Bannister’s magic-mile performance from 1954 had inspired me nine years after the fact. And from that moment on, in every cross-country race or mile run at our annual track and field day at Agincourt Collegiate, I felt as if I might one day match his achievement.

And what an achievement! On that May 6 morning in 1954, Bannister was still in training. I mean, he was still sweating it out as med student in a hospital in London. He’d boarded a train, travelled to the Iffley Road track at Oxford University. And there, while about a thousand people looked on, he’d run in a mile-long competition with his track teammates Chris Brasher and Christopher Chataway, and broken a world record. He’d broken the four-minute mile.

“The man who can drive himself further once the effort gets painful,” Bannister wrote later wrote in his memoir The Four Minute Mile, “is the man who will win.”

Then, several months after he’d broken the finish-line tape at Oxford, Bannister travelled to the Commonwealth Games (then called the Empire Games) in Vancouver to face his rival at the time – John Landy. Landy had broken Bannister’s 3:59.4 record in June 1954. So that set up a confrontation in Canada, the so-called “Miracle Mile.” The two athletes ran neck and neck through three and a half laps, when in the stretch Landy looked over his left shoulder just as Bannister passed him on the right to win.

Roger Bannister died this week at age 88.

Every autumn I ran cross-country races between halves during our high school football matches in Scarborough, and each springtime when I was allowed to wear that one-and-only time, running spikes, and pull on that tank-top jersey with my school colours across the chest, I felt like Roger Bannister running the miracle mile.

Until that phone call in 1980 when, as the writer on a half-hour TV documentary show, I managed to speak with Sir Roger Bannister and ask him for an interview. When he realized we intended to fly from Canada to Britain to do the filmed interview, he said, provided it didn’t interfere with his responsibilities at a London hospital, that would be fine.

I think I’ll always remember arriving – the cinematographer, sound technician, interviewer, and I (the researcher/script writer for the show) at his residence in Soho. His wife Moyra answered the door and directed us into their parlour where we set up our camera, lights, microphones and began the interview. As I recall, while dressed in a jacket and tie, and speaking in perfect Oxfordian English, the man who for several months in 1954 was the fastest long-distance runner on the planet, seemed more interested in talking to us about breakthroughs in his neurological practice, than breaking the four-minute mile. Even 30 years later, he seemed to downplay his achievement.

“However ordinary each of us may seem,” he wrote later, “we are all in some way special, and can do things that are extraordinary, perhaps until then, even thought impossible.”

The same way Roger Bannister had inspired me as a 14-year-old at the annual high school track meet in east-end Toronto, it was Dr. Bannister who’d told us in his rear-view mirror, that every woman and man has the ability to be exceptional. I guess I would have expected nothing less. Incidentally, at the track meet in my final high school year, in 1968, I broke a personal barrier – I ran a sub-five-minute mile.

Thank you, Dr. Bannister for sharing your spotlight of fame.

Swedish runner Gundar Haegg’s mile time of 4:01. 4 had stood for nine years, but in 1954 Bannister, Australian rival John Landy and others were threatening to break it. “As it became clear that somebody was going to do it, I felt that I would prefer it to be me,” Bannister told the AP.