About five years ago, I travelled to Kitchener to help a Second World War vet celebrate his 90th birthday. Harry Watts had served as a dispatch rider, a.k.a. motorcycle messenger, in Italy and Holland, 1943-45. Suddenly, during the birthday wishes and cake cutting for Harry, members of the Canadian Army of Veterans (CAV) pulled up on motorcycles to pay tribute to Harry, their eldest member.

“We’ve come to help you celebrate, Harry,” the CAV riders said.

“Thank you, brothers,” said Harry, his eyes welling up with emotion.

Before long, the gathering simmered down into a series of quieter conversations as Harry moved around the room from table to table receiving congratulatory birthday hugs and kisses. Meanwhile, the CAV riders quietly moved to a patio outside and chatted among themselves. I asked if I could join them and they welcomed me. And I just listened.

All four of the men had served in the Canadian Armed Forces – as I recall in Bosnia-Herzegovina, 1992-95. They were pretty upset about their experiences, and not just about what they’d witnessed. In this case, they had a bone to pick with the federal government for the way it had treated them with regard to recognition, pensions and counselling.

Most of them readily admitted to suffering and coping with post-traumatic stress disorder. At least, they said, the country had some understanding of the problem, and it wasn’t as if they were coming out of the closet about their PTSD.

“There’s no shame in operational stress injury,” one of them told me. “We just need the system to get it!”

“Getting it” has remained the problem for over a hundred years. Until recently, when more aware officials at Veterans Affairs Canada have responded to veterans’ PTSD needs, not directed them, ex-servicemen and women have had to fend for themselves. And not always successfully.

I remember my conversation with Jim McKinny on his backyard patio in Saskatoon, in 1997. McKinny completed a full tour of duty with the Royal Canadian Horse Artillery in the Korean War. Coming home in 1953, when his outfit disembarked the train in Winnipeg, the entire unit formed up at the railway station and marched to the city cenotaph. Jim felt real excitement, knowing his parents and girlfriend Lee had come from western Manitoba to welcome him home.

“But I couldn’t face Lee for nearly a month,” McKinny told me. We only lived 23 miles apart, but I just couldn’t handle people any more.”

Only when he learned that the newly formed Korea Veterans Association of Canada had established a chapter in the basement of the local Legion, did McKinny come out of his mental fog. Eventually, he and Lee got married, but he said, “Korea made me a social misfit.”

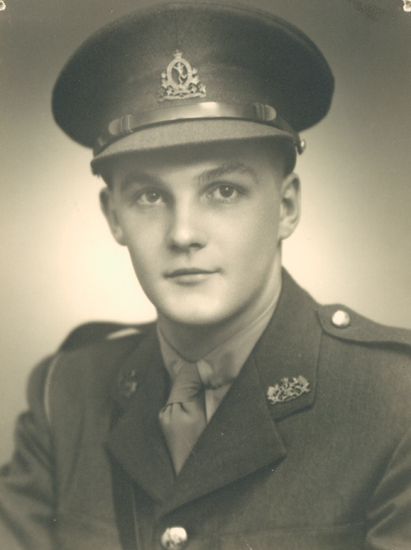

In 2003, when I sat with D-Day veteran Don Kerr, a few hours of interview illustrated to me that the former signals officer had managed to keep his Second World War demons at bay. In the course of our talks, however, Kerr described landing in Normandy on the morning of June 6, 1944. He recalled landing craft clogging the shoreline, shells falling from the sky, and machine-gun fire coming at him from Germany shore positions.

“You’re 21 years old. You’re scared stiff,” he said. He described coming across a jeep with a British captain dead in the driver’s seat. Don gestured as he described gently lifting him out of the jeep, laying him on the beach, piling his own equipment into the empty jeep, and driving toward the fighting ahead of him. He told me he’d never gone back to Normandy. He couldn’t even watch the movie Saving Private Ryan without breaking down.

“Bullets flying, bombs landing. Just utter, utter chaos,” he said, visibly shaking. “That’s why guys don’t talk about it.”

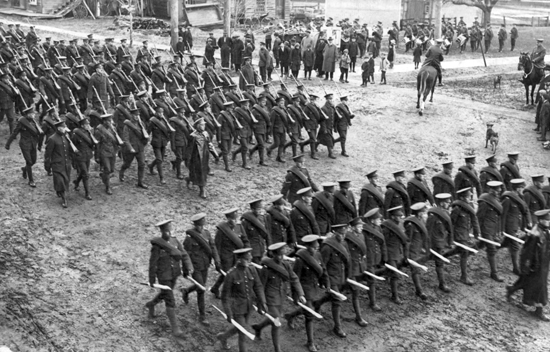

If little or no qualified help existed for Second World War and Korean War vets coming home, virtually none existed for Sam Sharpe following the Great War. A man who had always led by example – as a lawyer, church elder, and Member of Parliament – Sharpe had created, underwritten, and commanded the 116th Ontario County Battalion by leading it into battle at Vimy and Passchendaele in 1917.

But with fewer than a tenth of his regiment intact by 1918, and distraught because of that, Sharpe was quickly spirited away from the front and home suffering from “shell shock,” they called it. In Montreal, alone in hospital, the man who’d always led, had lost his way. He took his own life, and for that act, was forgotten and never recognized either for his service or his war wound.

Tomorrow, across from the Uxbridge cenotaph, the community will unveil a statue of L/Col. Sam Sharpe, created by artist Wynn Walters. It won’t depict him on a war horse or marching at the vanguard of his battalion. It will show him in the more vulnerable state in which battle-weary warriors no doubt often find themselves. Tomorrow’s event recognizes that one can take a soldier from a war zone. But the opposite is more complicated.

It’s time for all of us, as the Bosnia vet said, “to get it!”

We were fortunate to have the chance to get to know both Don Kerr and Harry Watts on your trips to Europe, Ted. Thanks for the memories.