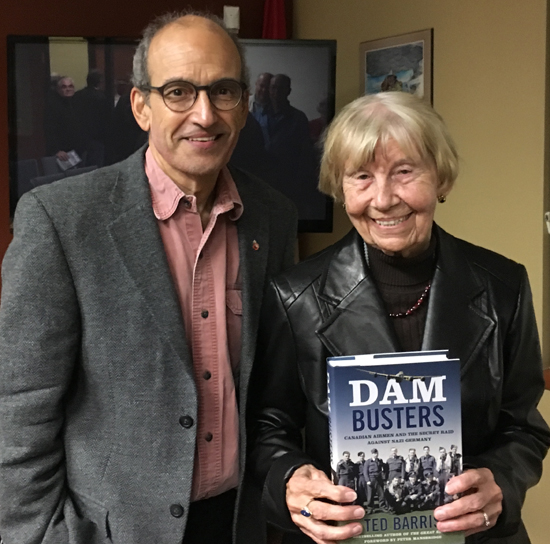

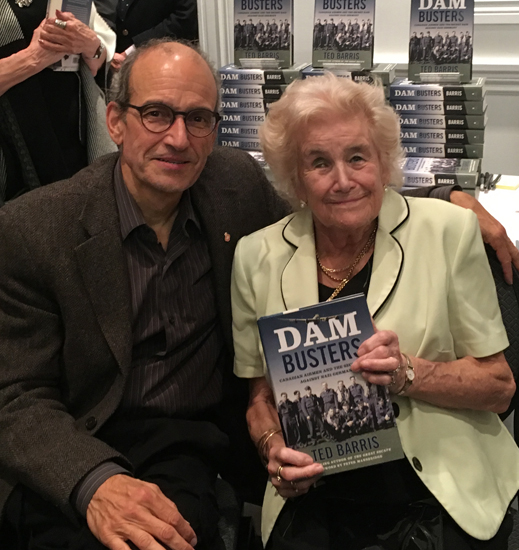

She’d sat pretty quietly a few rows in front of me – a woman with an intent look, a tailored leather jacket and a sparkle in her eye. Older than many in the room in Orillia where I spoke, her eyebrows responded continuously to my story – curving up when it was humorous, down when sad. When my talk was over, a man at the back of the room pointed out the very same woman and indicated she was his mother-in-law.

“She worked in war munitions in the Second World War,” he said, “but her most important work was in quality control at Victory Aviation.”

“You mean where they built the Lancaster bombers?” I asked.

“Ask her,” her son-in-law said. “And she’ll tell you she was in charge of rivets.”

And everybody in the room chuckled at the idea of something so small being supervised and analysed. It occurred to me to say, “the devil is in the details,” but I hesitated and considered the impact of what Dorothy Taylor accomplished three quarters of a century ago.

In a brief conversation after my presentation, she described her quality-control job at A.V. Roe, in Malton, Ont., where they built the massive Lancaster bombers that were then flown by Commonwealth aircrews of Bomber Command against targets in Nazi-occupied Europe.

With Remembrance Day just a few weeks away, I’ve spoken to and listened to those in my audiences reminisce about their experiences as Canadians serving in wartime situations. Remarkably, I’ve run into countless stories of those whose work – not necessary on the front lines – contributed to the war effort and to the ultimate success of Allied efforts during the Second World War.

At another talk to the Halton Canadian Club a few weeks ago, I met Ann Barnes whose mother had worked with maverick British engineer and aircraft designer Barnes Wallis, chief designer at Vickers Armstrong in its aviation division.

He’d designed the first British dirigibles, the famous Wellington bomber, and for a mission known as the Dam Busters raid, he’d designed the bounding bomb to bring down the hydro-electric dams of Nazi war production in the Ruhr River valley. Elsie Lacey, Ann said, had worked feverishly as a draftswoman at Vickers for Wallis.

“He was a taskmaster,” she said, “but her work made a difference.”

Just last week, during an event in Hamilton, I met another woman with a story. Jo-Ann Tippett’s father had served during WWII in the nationwide air training plan in Canada that had churned out pilots, navigators, bomb aimers, flight engineers, wireless radio operators, gunners, etc. for the air force. J. Raymond Tippett had trained navigators.

But in the race to assemble all the tools his students would need, the air force had neglected to include protractors – the devices used to measure angles, in particular those inside a circle – so his students could figure out directions via the stars, distances by airspeed, and elevations based on topography.

“He had to improvise with rulers and strings,” Jo-Ann Tippett said, “until the actual protractors finally arrived.”

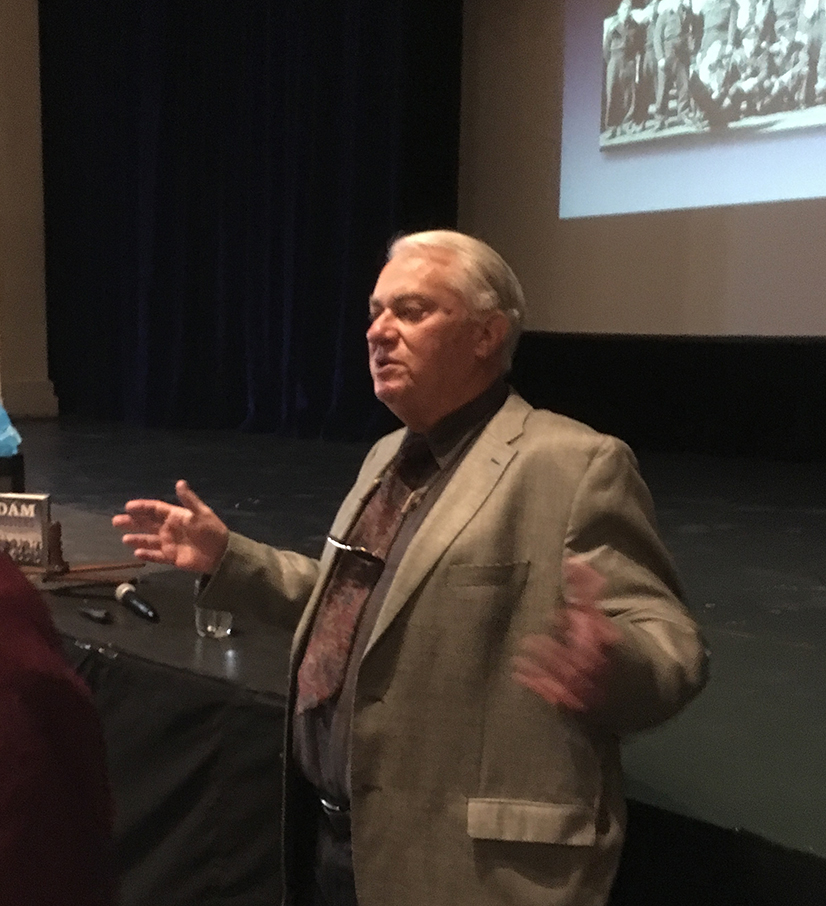

Talk about improvising, this week, I spoke to students at Lisgar Collegiate Institute, in Ottawa, about their school’s connection to the war. On its honour roll – former students who served and died in world wars – was the name Lewis Burpee.

After graduating from Lisgar in the 1930s, he studied architecture at Queen’s University, then enlisted in the RCAF and flew on the same dams raid for which Wallis had created the bouncing bomb; but Burpee did not survive the mission. As a surprise for the students, I managed to find Burpee’s son, Lewis Jr., who joined me and summed up his father’s wartime sacrifice.

“The details are these,” Burpee Jr. said. “Nineteen aircraft went out. Only 11 came back.”

Just before the lady with the expressive eyebrows left my talk in Orillia, a few weeks ago, I quizzed her about just what being in charge of rivets actually meant. How could something so small mean so much?

“Well, I used to run my hands over any points where a rivet went into the Lancaster fuselage,” she said, “and if it wasn’t perfectly smooth, it was my job to have that rivet replaced.”

So, I guess, the devil WAS in the details. If Dorothy hadn’t been so fussy about rivets, Elsie about draft work, Tippett about protractors, and Burpee about defying the odds, the results might have been vastly different.