From the highway, it looked like any other country shop. A big hand-made sign greeted us. Sculpture and other folk art dotted the grounds outside the building. Wrought-iron decorations covered the façade of the gallery. We met the proprietor at the door and he invited us in, through the showroom and into his workshop in the back.

“Be careful,” he said. “There’s stuff everywhere.”

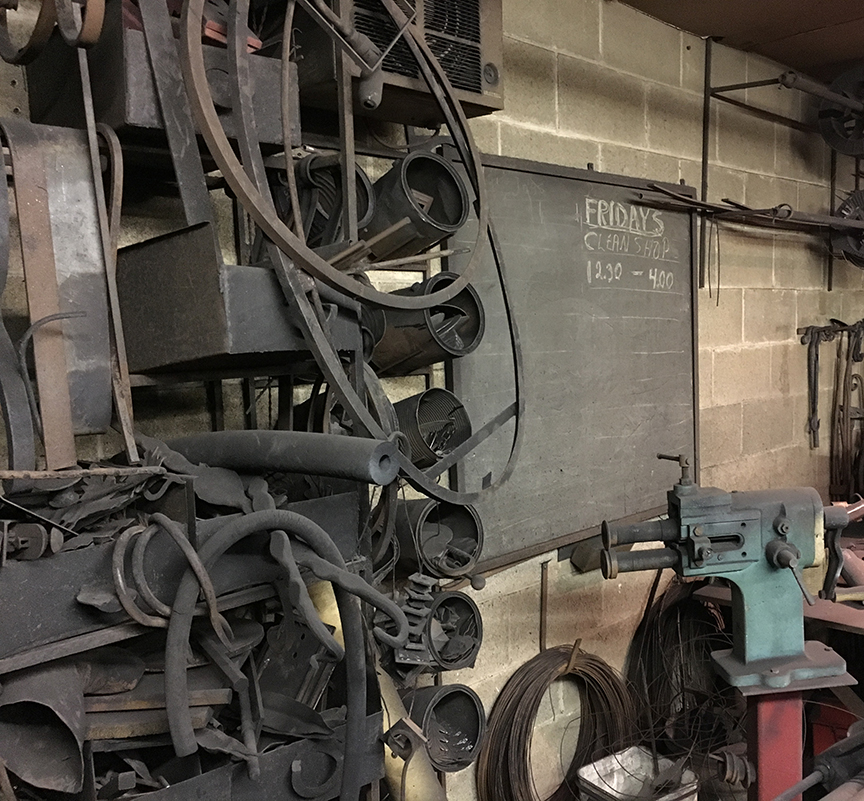

He wasn’t kidding. The back shop, like an over-sized garage, was dimly lit; it took a second for the eyes to adjust to dinginess. The door barely opened for the raw steel stacked everywhere. There was a forge and makeshift chimney on the back wall, complete with stacked bags of coal for burning. Hooks on the walls held raw steel – some ring-shaped, some blocks, but mostly long rods – ready for sculpting.

And all around the shop, sat huge, unfamiliar pieces of heavy machinery that the artist used for cutting, bending, grinding and polishing the steel. To my uneducated eye, the shop was a mess. But once he explained the way he worked the steel into pieces of art – lamps, shelving, wine racks, and other household accessories – I realized everything was organized in piles according to plan.

“It looks a little confusing,” said Matt, the owner operator of Artisan’s Gallery in Muskoka, “but it works.”

It wasn’t long before his words reminded me of other workplaces I’ve known. To the outsider, the working environment of someone with a specialized craft or profession seems totally foreign, until the contents and the arrangement of the contents – whether an industrial site or a functioning office – are explained.

I thought of my first ever visit to an industrial shop back in elementary school. I think it was about Grade 7 or 8 when we travelled from North Agincourt to C.D. Farquharson for classes in woodworking, sheet metal and plastic craft. On the very first day we entered the shop, I remember our teacher barking at us.

“Don’t touch anything!” he warned. “If you want to commit suicide quickly, you’ve come to the right place.”

And as we absorbed that frightening provision on our introduction to industrial arts, we all looked about the room to take in the machinery and the piles of stuff. Everything seemed organized, but unless we knew anything about lathes, drill presses, band saws or torches, it was all just piles of stuff.

My first ever job as a copy boy at the Toronto Telegram newspaper in 1968 hit me the same way. Of course, there were reporters’ desks everywhere; that was normal. But each desk, according to the specific working habits of the reporter was stacked high with clippings, press releases, rulers, pencils, glue pots and yellow writing paper (in triplicate with carbon paper between each layer). And overhead hung these strange-looking tubes, like the tentacles of an octopus, crisscrossing the room and then disappearing either into the floor or up into the ceiling.

“Those are suction pipes,” a senior copy boy told me. “Put copy inside this little tube (a clear, cigar-shaped container), pop it into the suction pipe and zip, it shoots to the production room.”

Once again, until I understood what all the piles and gear were, it was all Greek to me. And speaking of Greek, I can also vividly remember my summer job as a busboy in the back of my uncle’s Double T Diner in Baltimore, Maryland. It was the mid-1960s; it was oppressively hot, and I worked with mostly African-American staff in the back – dishwashers, short-order cooks and waitresses.

I very quickly learned my relationship with the piles in that working space too. There were piles of cutlery, dishes, glasses, cups, saucers, pots and pans – and it was my job either to clean them all, sort them all, or deliver them all to the cooking staff preparing the next meals of the shift. The piles of dishes and food governed our lives 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

Today, my home office looks not unlike that sculptor’s workshop in Muskoka or that Greek diner in Baltimore. Of course, there are shelves and desks filled with the communications equipment of my writing profession. But everywhere in between there are piles – piles of magazines, piles of clippings, piles of correspondence, piles of manuscripts, and piles of reference books – mostly on the floor. Getting to my desk is kind of like crossing a minefield. Again, to the outsider, the piles look a mess. But to me they’re organized according to priority and job function.

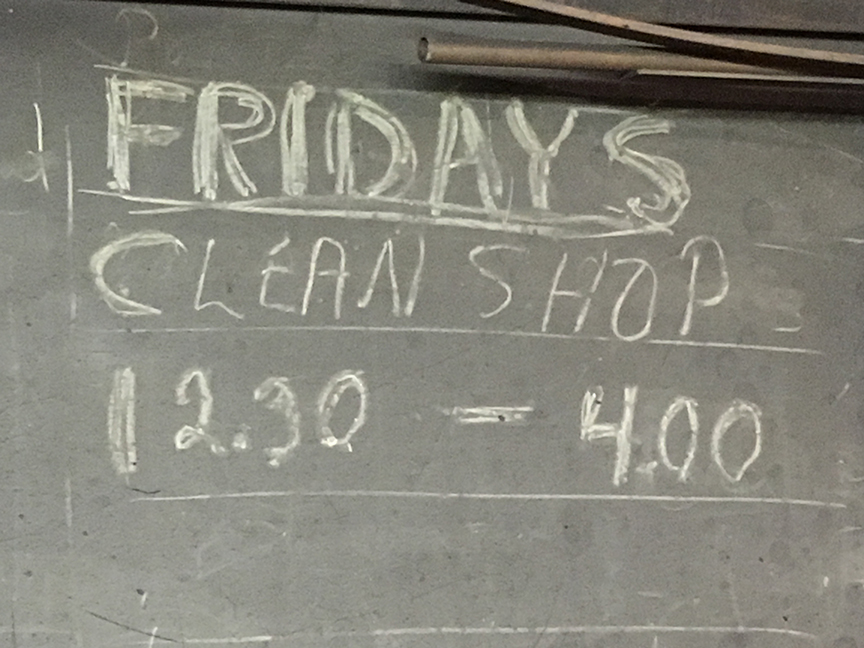

There was one thing I spotted amid the piles at the Artisan’s Gallery, however, that I don’t have in my office. On one of the steel workshop walls, Matt has hung an old blackboard. On it is a chalk message he’s posted there, I guess as a weekly reminder to deal with the piles.

There was one thing I spotted amid the piles at the Artisan’s Gallery, however, that I don’t have in my office. On one of the steel workshop walls, Matt has hung an old blackboard. On it is a chalk message he’s posted there, I guess as a weekly reminder to deal with the piles.

“FRIDAYS. CLEAN SHOP. 12:30 – 4:00,” it says. I’m not sure if it’s a rule or wishful thinking. It would be in my workspace.