He took the pass. He moved around the arc on the floor around the basket. There were four seconds left in regulation time. And all spectators in the building were on their feet, leaping and screaming. At the corner of the offensive end, he turned, jumped and launched the ball.

“Is this the dagger?” one commentator shouted into a mike.

Then, with the ball in the air, the final buzzer blared. The ball landed on one side of the rim, then bounced to the other side, bounced a third time, dribbled a fourth, and then dropped through the hoop. “Yesssssss! Game! Series! Toronto Raptors have won!” the announcer screamed finally.

And before the stands had emptied at the Scotiabank Centre last Sunday afternoon, every pundit in the GTA was commenting that for a generation people would be asking, “Where were you when Kawhi Leonard threw the game- and series-winning basket against the Philadelphia Seventy-Sixers?”

Not only that, some immediately compared the moment to Toronto Blue Jay’s José Bautista’s bat flip home run against the Texas Rangers in 2015? Another said that Kawhi’s buzzer-beater was even more momentous than Joe Carter’s “Touch ’em all Joe,” homer in the Blue Jays’ World Series win in 1993.

OK, I get it. But hold on a second. Does it have to be the biggest point, the most important score, the most legendary moment? What about Jozy Altidore’s 67th-minute goal in the Toronto Football Club’s 2017 first ever MLS Cup victory?

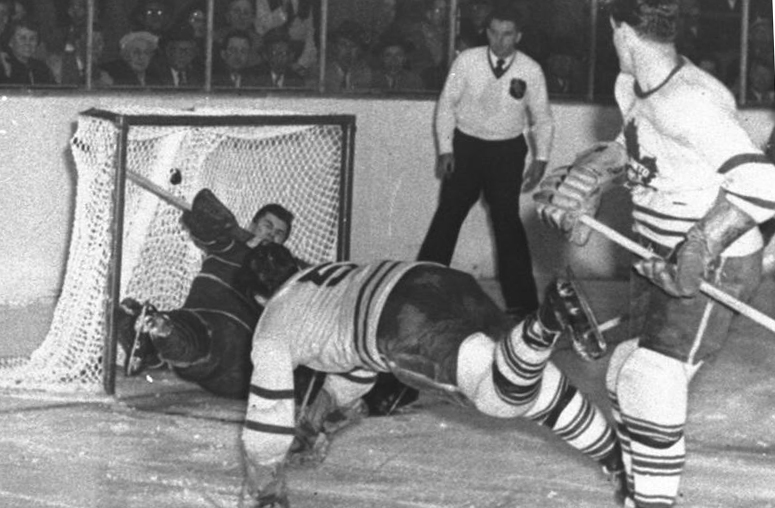

What about Bobby Baun’s broken-ankle goal that earned the Toronto Maple Leafs the 1964 Stanley Cup?

Or, just as iconic, how about the Bill Barilko overtime goal, that gave the Leafs the Cup in 1951? Why is it, we’re expected to instantaneously place everything that happens into a greatest, wildest, most unique category?

Whatever happened to sober second thought and maybe – on analysis – the realization that what just happened may notbe the greatest, wildest, most unique ever? What is it with our expectation that we always have to have the definitive answer right away?

I remember the assassination attempt on President Ronald Reagan, back in 1981. The president had just emerged from a luncheon speech and was responding to reporters’ questions en route to his limousine. John Hinckley Jr. began shooting at the president’s entourage. First reports said that James Brady, Reagan’s press secretary, had been shot, but that Reagan had not. In the live news coverage of the moment, ABC TV anchor Frank Reynolds is heard shouting at an individual off-screen.

“Speak up,” he calls. Then, Reynolds, a close friend of James Brady’s, is told that Brady had died of a head wound in the shooting. Then, Reynolds is told the death report is erroneous, and on-camera the news anchor becomes visibly upset and reacts.

“Let’s get this nailed down … Somebody … Let’s find out!” he shouts live on air. “Let’s get it straight, so we can report this thing accurately.”

When I first got into broadcasting, I worked the graveyard shift on the radio. Because our resources were limited, our time even more so, and our reporting staffs non-existent, all too often those of us writing newscasts resorted to pulling content from the Broadcast News or Canadian Press wire service.

Our copy rolled out of the teletype machine, like toilet paper from a dispenser and during those seconds we had before we went live to air, those of us in the newsroom simply resorted to rushing to the news wire machine, scrolling off a sufficient number of stories, tearing them from the machine and dashing to the microphone to read what was on the paper.

The process was known as “rip and read,” as we grabbed the paper and read it cold. In other words, nobody vetted the stories. Nobody considered their accuracy or whether they were factual or not. And nothing was edited unless live on the fly. And we thought that kind of journalism was bad.

Today, if a news agency cannot get a piece of news video recorded on a cell phone, edited into a 10-second clip, scripted and streamed on air on a news application in micro-seconds, the newsroom, newspaper, broadcast outlet or online news source is considered a failure. If it’s happening now, you’d better have it online a second later.

I understand how important getting your news instantly (and everything else for that matter) has become. I recognize that young people (and others) demand immediate gratification. And we all seem to pander to that perceived need.

But do you think maybe we could pause a second or two, and introduce some reflection and perspective on these things before passing judgement? And when we do that, maybe we’ll find that Kawhi Leonard’s game-ending shot last Sunday has significance, yes.

But so too does Jozy Altidore’s goal, and Joe Carter’s homer and Bill Barilko’s Cup-clincher. Use superlatives, but keep them in perspective.