At first, it didn’t look like much. From a distance the building looked, well, like a barn. It even had a silo. But on closer examination, I could see signage and some outdoor exhibits. No animals. No straw bales. In fact, when I looked up inside the silo, there was no silage, but a scale model of a vintage airplane.

“There are artefacts in here that you’ve never seen before,” said John Lawson, the chair of the Montreal Aviation Museum. “Welcome to my second home.”

Airplanes and aviators have always been a guilty pleasure in my life. It started with plastic model airplanes I assembled and then painted or authenticated with affixed decals. The Lancaster. The Spitfire. The Avro Arrow. Then, I read all the classic aviation books: Reach for the Sky, A Thousand Shall Fall, 12 O’clock High and Piece of Cake. So, when the Canadian Aviation Historical Society invited me to speak to its annual general meeting in Montreal, last weekend, I didn’t dare miss one of the side trips while billeted in the Sainte-Anne-de-Bellevue area. John Lawson was a fellow delegate during the AGM and led us through the Montreal Aviation Museum (MAM).

He and his fellow volunteers – because most aviation museums these days are run entirely by volunteers – showed us past the museum’s 1927 Fairchild photo-survey plane, its 1935 Noorduyn Norseman bush plane, and its 1942 Bristol Bolingbroke bomber, still under reconstruction.

But clearly Lawson’s favourite he left to last. “Piece de résistance,” he said. “Our Blériot XI.” The single-seat, mono-wing aircraft looked like little more than a glider with its open fuselage, open cockpit had landing gear that seemed more like a set of buggy wheels than an aircraft undercarriage; it was the centrepiece of the MAM. Clearly, Lawson was in love with this magnificent reproduction. Me? I was interested in its story.

Louis Blériot, after whom the plane was named and its first operator, flew over the English Channel on July 25, 1909 – 110 years ago. It was the first heavier-than-air aircraft to connect France and England across the Channel. In the true spirit of aviation pioneering, without the aid of a compass, Blériot took off into the sunrise that morning and buffeted stiff winds for 36 minutes, landing in Britain with a controlled crash landing. He survived, earned £1,000 as prize money, and became an instant celebrity. Here’s his diary entry after the flight:

“I headed for this white mountain, but was caught in the wind and the mist,” he wrote. “I followed the cliff from north to south, but the wind, against which I was fighting, got even stronger. A break in the coast appeared to my right, just before Dover Castle. I was madly happy. I headed for it. I rushed for it. I was above ground!”

I’ve always enjoyed the thrill of seeing classic, vintage and antique aircraft. Like all the people I call “rivet counters” in the world, I do enjoy seeing the planes, touching them, smelling them, and sometimes witnessing them airborne at air shows. But I’ve always felt more excited by the face of aviation. By and large, such human stories of aviation are largely overlooked or lost. And at the Montreal meeting, I learned some new ones.

Among the other presenters during the AGM, Dick Pickering offered anecdotes about his dad, Doug Pickering, flying bush planes into the far north; in every photograph Dick showed, whether in the bush or on the streets of Montreal, his dad was always wearing a tie. And aviation author Anne Gafiuk offered the wartime story of an RCAF Canso crew that had to force land on an ice flow in the Atlantic and survived for days in a dinghy before dying of exposure. “Such war stories are heart-rending,” she said.

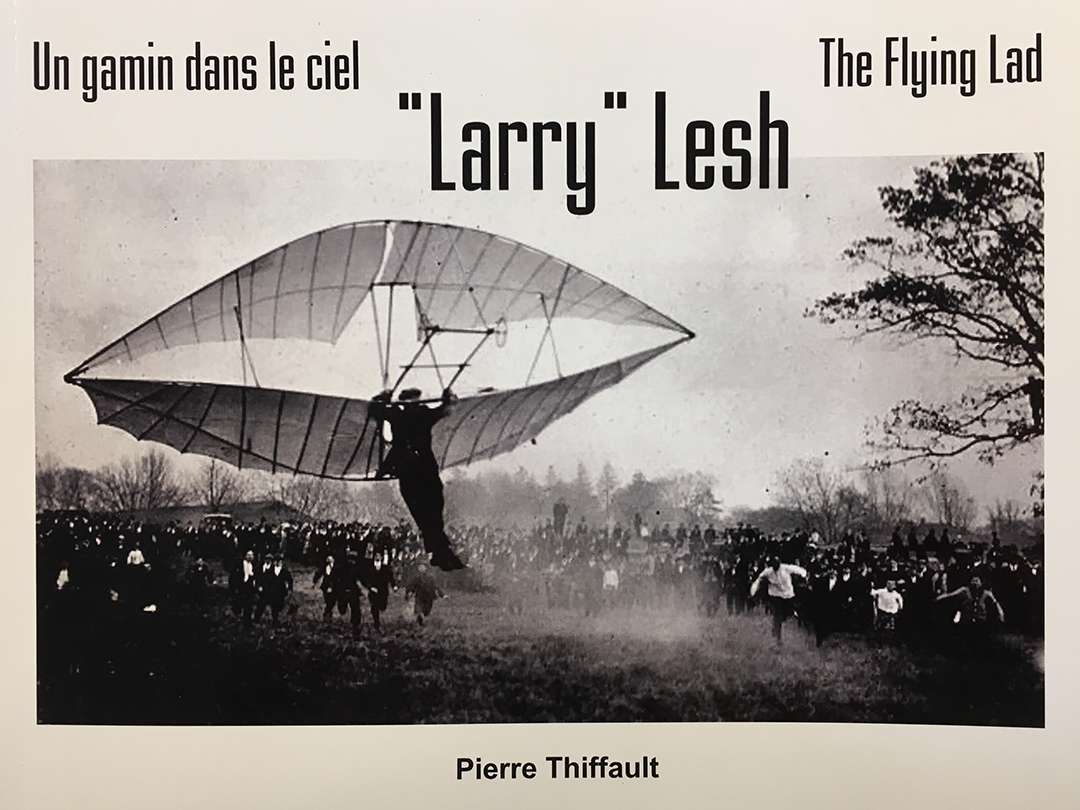

Then, there was the tale of the so-called “flying lad.” Based on his own research, author Pierre Thiffault (Larry Lesh, The Flying Lad) dug into the history of a youngster named Laurence Jerome Lesh. Just 11 years old when the Wright brothers flew their first airplane, and caught up in the romance of flight at the turn of the 19th century, Larry Lesh managed to search out Quebec flying machine expert Octave Chanute, who was recruiting young capable aviators to test fly his gliders.

Lesh proved himself to be Chanute’s chosen glider pilot. He made a series of test flights, but Lesh’s date with destiny occurred on August 21, 1907. Towed by and tethered to a motor boat on the St. Lawrence River and launched from Montreal’s Dominion Park, Lesh hung from the glider some 60 feet in the airborne over the river for some 24 minutes.

“(It gave the) sensation of flying,” Lesh wrote, “no petty adventure!”

Just like French aviation pioneer Blériot, Canadian Larry Lesh, had to endure a crash landing – on the water – but he survived it and other crashes to perpetuate his “flying lad” nickname – at 16, a Canadian aviation legend we’ve never heard of.

I came across your article while I was looking for photos of Larry Lesh. I’m one of his many great-grandchildren, Heather Leonard (nee Lesh). My dad is Laurence Jerome Lesh III and he is still alive and well and living in Texas near me.

I communicated with Mr. Thiffault via email when he was working on the biography of my great-grandfather, as did my father. Larry Lesh Sr. is actually not Canadian, but American. He was born October 29, 1892 in Fort Madison, Iowa and passed away on Dec. 15, 1965 in Fort Meyers, Florida, where he had retired. He did have some times with Canada, as you pointed out, but he was married in Ontario as he was living there at the time. His wife, my great-grandmother Gail McCreary, was from New York. He also spoke French fluently.

Larry held several patents for boat and helicopter designs. In his later years he was an amateur painter. His grave marker in Fort Meyers notes that he is one of the Early Birds of Flight. Thank you for bringing attention to my great-grandfather. He was a fascinating man and is one of the lesser known pioneers of early aviation.

Hi Heather…

How kind of you to take the time to write me a note about my Barris Beat column from May 2019. And how wonderful to know that Laurence Jerome Lesh has living relatives to carry on his memory. Until I attended that national convention of our Canadian Aviation Historical Society in Montreal two years ago, I was not aware of his inspiring story. And to know that you continue to trumpet his contributions is a treat. We tend to get so swept up in the tales of the Wright brothers, the Silver Dart, and the usual stars of early aviation command, that we forget that pioneers are often right in our own backyard. I’ve made a career of writing about many – like your great-grandfather – who remain overlooked but so pivotal to our progress as human beings, adventurers, patriots, and men and women in the service of their country. Thanks for correcting the birth details. And keep on telling the story of “The Flying Lad.” He would be proud…

Best… Ted.