It was a critical moment. My teacher friend Tish MacDonald stood behind the tombstone collecting her thoughts. Several dozen of her students from Uxbridge Secondary School quieted down in front of the headstone with the inscription, “Rifleman, Donald McKay Barnard,” etched into it. They waited for their teacher to offer testimony. They waited for Tish to speak her truth.

“This is why we come from Canada,” she said, barely holding back tears, “to respect what was lost here and to honour what men like Fred Barnard and his brother Donald sacrificed as young men.”

Tish MacDonald has visited Rifleman Barnard’s grave each time she’s led Remembrance tours with her students to France. She has wisely used such moments as a teaching tool to build her students’ awareness of Canada’s role in the war. But I think she’s also repeated the ritual because she’s living up to the bargain she and Fred Barnard have shared all the years they’ve known each other.

Each time she visits that stunningly beautiful cemetery at Beny-sur-Mer just up from Juno Beach, she brings the greetings from one Barnard brother who survived the war to the other who did not. In so doing, she carries the torch the Barnard brothers carried there 75 years ago this past spring.

“It gets tougher each time,” Tish confessed to me.

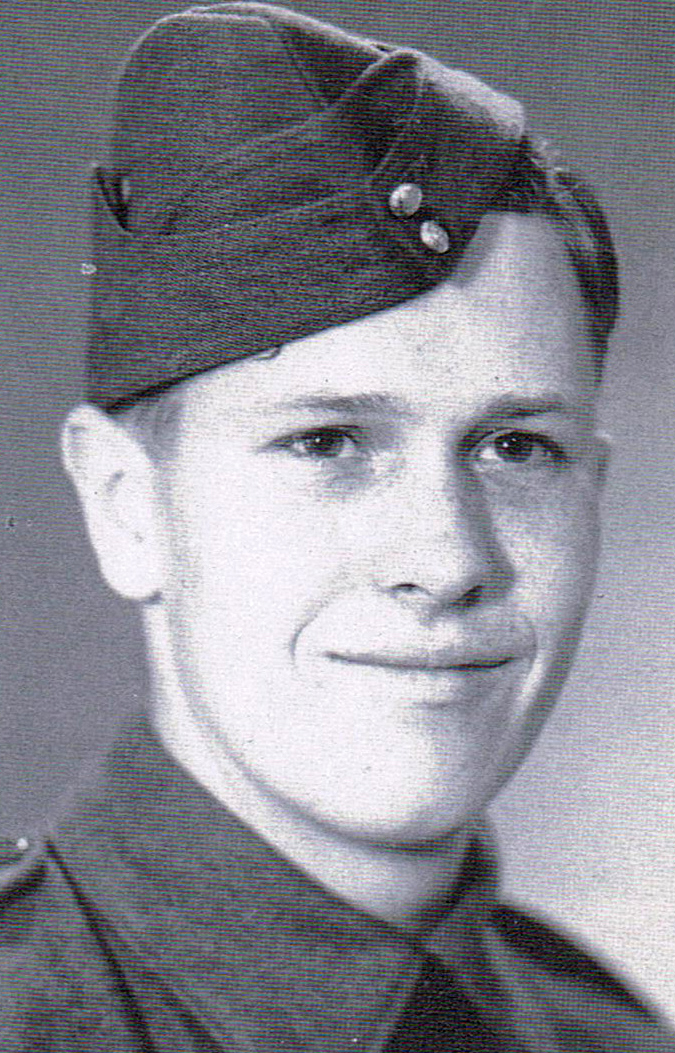

It will be even tougher this week because now Fred Barnard is gone. He died in hospital early last Friday morning with his daughter Donna at his side. He was 98, and died as he lived, modestly and shunning any attention for his past accomplishments, not the least his landing in the first wave with the Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada on the beaches of Normandy on June 6, 1944.

There’s a portion of that torch Fred has passed to me as well. As I have described before in my columns, he and I met one day 16 years ago in the local bank. We were queued up waiting for a teller. It was entirely coincidental, but he offered me his memories of D-Day and the Normandy campaign just as I was writing that very story in a manuscript for a book about the Canadians’ experience during the Invasion. Fred made it off the beach, but his younger brother Don did not. It’s a story Fred shared with me one Saturday afternoon in 2003.

“By the time we got to the wall (at Bernières-sur-Mer) Fred told me, “bodies were floating everywhere, including my brother’s. … But our orders were to keep going.”

Not only had Fred lost his brother on June 6, but more than half his “B” Company and its sister “A” Company had been decimated – 138 of 240 men, 63 dead and 75 wounded. In fact, 50 per cent of the officers were gone and that left junior ranks such as Fred’s leading those who’d survived the beaches. A few weeks later, when Fred’s platoon leader, a sergeant, was wounded, he turned to Fred and told him: “You’re in charge now.”

The torch had been passed to him. Cpl. Barnard carried it as far as he could in Normandy. On August 10, during the battle of Falaise Gap (75 years go this month), Fred’s platoon was boxed in by enemy artillery fire and tracer bullets kept chewing up his position. “I could actually see the bullets coming at me,” he said. “Then, an artillery shell landed about 50 feet away and a piece of shrapnel hit my foot. And that was it for me. I never went back.”

Fred Barnard was loaded onto a stretcher, carried by jeep to an aid post and flown to England in a DC3 transport plane. But Fred chose never to go back, not back to Europe, not back to Normandy, not back to his brother’s grave. Perhaps he left that to another generation, Tish MacDonald’s and mine. Fred told me back in 2003 that he’d enlisted in the Canadian army in 1941 after seeing newsreel film at a movie theatre in Toronto.

“I didn’t like what the Nazis were doing … bombing London, putting Jewish people in concentration camps. I didn’t like the hatred,” he said. “I had to do something. Somebody had to do it.”

Earlier this spring, on the 75th anniversary of D-Day, our community responded in kind. Thanks to Tish MacDonald, the Legion, fellow veterans and the township, Fred was honoured right there on his front porch. One of our grandsons, Wyatt, was invited to step forward and thank Fred on behalf of fellow students; Wyatt was extremely proud.

Coincidentally, on Friday, when Fred died, I received a photograph of our youngest grandchild wearing a T-shirt with “Juno Beach” across the chest. Tully is only two and doesn’t understand its significance. I guess that will be up to me to explain.

I’ll do my best, Fred, to pass your torch along.

It was March break of 1985 when I first visited Vimy Ridge and I will never forget how somber the experience was vowing to visit again should I ever returned to France. In 2013, I did with my wife and some friends in tow insisting that we visit Vimy. It again was an incredible experience. June of 2019 we had the opportunity to travel to France once again and we toured Dieppe, Dunkirk and Juno Beach. The most heart wrenching experience of the trip was finding my Great Grandfather’s WWI war grave in the small town of Barlin France just west of Vimy Ridge where is was buried in 1918. Even now I can barely see through the tears in my eyes as I type this.

Vimy was not destroyed by the Nazis in WWII because it was a tribute to the losses of war, something that Hitler recognized and saved that monument for that reason.

November 11th will never be the same knowing that part my DNA rests in a wargrave in France.

Thank you Ted for giving these stories from the wars faces and names.

With Gratitude.