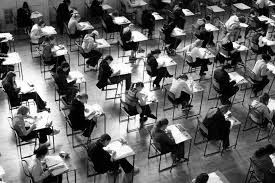

They crammed us into a single hall at the school. Often it was the high-school gymnasium filled with rows and rows of movable desks and chairs. We were allowed pencils, an eraser, a ruler and limitless sheets of what we used to call “foolscap” paper on which to write our answers. In came an adjudicator, who announced the name of the exam, the time available to complete it and strict guidelines for decorum during the exam.

“If we catch you cheating,” the adjudicator announced, “we will disqualify your mark. You will fail the term.”

In my day – back in the 1960s – these meat-grinding assemblies to test the cumulative knowledge of students at year’s-end were known as “Departmentals.”

In other words, as our high-school experience came to a conclusion (at that time Grade 13), we wrote such exams for the core subjects of English, French, history, mathematics and the sciences (biology and chemistry) in order to pass. And our performance during these Departmentals determined our future at university, community college or technical school. To us mere students, that pressure seemed like a date with the hangman. No. To fail a Departmental was a fate worse than death. Or at least that’s the way it seemed.

Just how real that anxiety and fear have become in Ontario’s high schools and universities emerged at the University of Toronto late last winter. Students at the downtown campus of the U of T staged a demonstration in front of the president’s office demanding greater access to mental health counselling.

One of their own, a first-year student, had become so stressed in his studies that he’d taken his own life. So, suddenly, his classmates and fellow freshmen began expressing their own state of mind, including Brian Hao, a first-year political science student.

“I’ve been dealing with depression and anxiety since Grade 10,” he told CBC Radio in March. But he admitted that studies and life at one of the most prestigious universities in the country, the U of T, had simply ratcheted up the tension and self-doubt. Hao went on to explain, during exams in his final semester at high school, that he’d seen a doctor to keep himself safe, “because suicidal thoughts were there.”

Certainly, cramming, writing exams, attaining grades sufficient to deliver entry to Canadian post-secondary education, affected us 50 years ago. I remember feeling crushed that I hadn’t managed to achieve honours grades in some of my subjects, particularly math and sciences.

Meanwhile, all my studious classmates were chuffed that they’d maintained their honours standing right across the board. I felt as if I’d let my parents and my teachers down by falling short in biology and chemistry. Of course, it was self-inflicted punishment and pain. But consider suicide? Not even close.

This past weekend, students again gathered at the Bahen Centre on the U of T campus to mourn the death of another classmate. It was the third suicide at that centre in the past two years. As a stopgap, the university installed safety barriers around the balconies and stairwells at the Centre.

Students left notes of condolence and sympathy, because for many of them it’s not a matter of keeping up with fellow students (as it was for me), but a matter of survival. One U of T computer science student explained to CBC how much more competitive university grades are today.

“In computer science (in the first year) you have to get in the high 90s to get into second year,” he said. “Of my 10 friends in the computer science program, only one will be eligible to graduate to the second year. Nine will have to drop out.”

In other words, while in the early 1960s, I might have become the one in 10 who didn’t score straight-As in my class, 50 years later, the university system is allowing only one in 10 to advance in a core program.

Why would a system grooming tomorrow’s leaders only want one successful graduate? What has become of Ontario’s high-school and post-secondary education that it inflicts an atmosphere of losing on so many young people? I’m not advocating that we water down the system. But on the other hand, I don’t think an inclusive, functioning society should demand that only one computer science genius succeeds, while it turns away nine other perfectly capable computer scientists.

Late in the 1960s, they finally dispensed with Departments in Ontario. In 1988, the province replaced Grade 13 with the Ontario Academic Credit (OAC), a fifth year for academic students and then phased that out completely in 2003. High school education was adapting to the times.

Clearly, entry level post-secondary programs also need to adapt. The world won’t be run by geniuses, but graduates who are challenged by and love their chosen field, but aren’t expected to become latter-day Einsteins in order to succeed.