I met a couple of teachers, a few years ago. At least, I came to know a little of their lives. There’s not much I can relate. They were both Polish. One was named Jan Ciechanowski, born in March 1882. And Jerzy Brem was born in September 1914, as the Great War began. They both came to the area of Poland, around Krakow, in 1941. Or, more correctly, they were brought there, to the small town of Oswiecim, which elite German armies then occupied. The Nazis renamed the place, Auschwitz. And here’s the way the Nazis’ records summed up those two teachers:

“Jan, number 11193, executed Oct. 29, 1941” and “Jerzy, number 10190, executed August 19, 1942.”

On Monday, Jan. 27, the 75th anniversary of the liberation of the Nazi death camp, named Auschwitz, I recalled my visit to that place seven years ago. At the time, I led a Canadian tour group to Auschwitz-Birkenau to meet teachers Jerzy and Jan and several hundred thousand other victims of that reign of terror during the Second World War. As all who visit this place, my fellow travellers and I passed through the gate with the infamous slogan posted above:

“Arbeit Macht Frei” or “Work will make you free.”

And then we entered one of the darkest places on earth, where Hitler’s henchmen herded, imprisoned, starved, tortured and then murdered countless thousands simply because of their ethnic origins, their racial background, their sexual preference, or, in the case of Jerzy and Jan, for being purveyors of knowledge that the Nazis decided had to be exterminated.

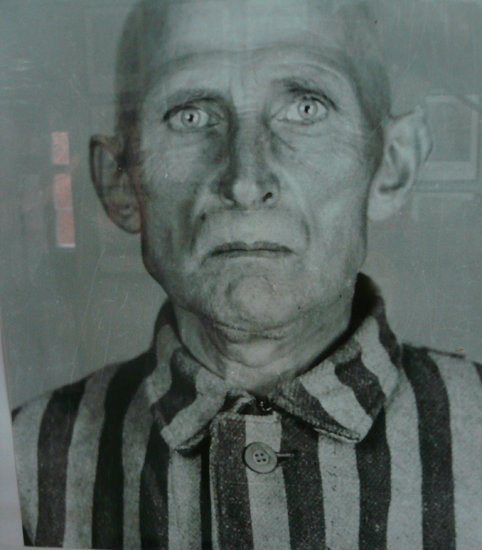

I found the photographs of teachers Jerzy and Jan hanging on a brick wall inside one of the blockhouses of Auschwitz prison. In the photos, their heads and faces are shaved of all hair. They both wear the striped prison shirts and numbered tattoos on their arms, forced on them by the Nazis. The process was designed to deprive them of everything, including their identities.

And yet, in their eyes, I saw a flicker of personality – perhaps the only thing their captors could not erase. Perhaps because he was younger, I saw in Jerzy a look of defiance, and in Jan, perhaps because he had more years, a look of knowing, as if, in spite of what he sensed was about to happen to him, there might be hope of a future better than his present. But it was all snuffed out in a torture chamber, a solitary cell, an executioner’s order and finally the ashes of a crematory oven there at Auschwitz.

As an antidote, that same day in 2011, I led my travel group to 4 Lipowa St., near the former Jewish ghetto in Krakow. It’s the address of a wartime enamelware manufacturer named Schindler. Yes, he was the man made famous by the Steven Spielberg, Academy-Award-winning movie “Schindler’s List.” It was there, that card-carrying Nazi, Oskar Schindler employed no fewer than 1,200 Jewish workers and saved them from the fate assigned teachers Jerzy and Jan.

“He employed me at this factory although he knew I would be useless to him,” one of those on Schindler’s list later reported.

And inside the former enamelware factory in Krakow, we not only found stories of those saved by a businessman with a conscience. We also learned how and why it was that teachers Jerzy and Jan were such a threat to Hitler and his regime. Among the exhibits inside Schindler’s factory, was the account of an interesting arrest. On Nov. 6, 1939, professors at the Jagiellonian University in Krakow faced the wrath of Nazi occupation. An S.S. officer described their crime:

“Your university has always been the source of malice and hostility toward the Third Reich,” he said. “We are going to take you to a POW camp and inform you of the real situation.”

The Nazis’ real situation was the capital punishment that professors Jerzy and Jan faced in 1942. Of 183 instructors arrested that November day at Jagiellonian University, perhaps half were interrogated, tortured and executed as criminals, when all they were guilty of was teaching the humanities, sciences, the arts and history to their college classes.

Adorning the outside of Schindler’s former enamel factory on Lipowa Street, in Krakow, were the photographs men and women whom Schindler had put on his list and saved. They survived because of the courage of one man. The rest – including the 1.2 million Jewish civilians imprisoned and murdered at Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp – did not have a Schindler to save them. In this week of the 75th anniversary of the end of the Nazis’ reign of terror, I pledge to teachers Jan and Jerzy using the words of author Meir Kahane:

“We have seen the mounds of corpses,” he wrote in his 1972 book. “We saw their outstretched hands, looked into their soul-searing eyes and heard them say, ‘Never again. Promise us. Never again.’”

I would like to add a small supplement to what you wrote. Jan Ciechanowski was my great-grandfather, he was indeed a teacher (headmaster of the school in Junikowo near Poznań). The Nazis sent him to Auschwitz for that, he talked to his colleague on a tram in Polish – just for that! Trams in Poznań at that time had the designation “Nur fur Deutsche” (only for Germans) and Poles could not use them, even though they were their property two years earlier. My great-grandfather knew about it and was just damn brave, unfortunately he paid for this courage with his life. He orphaned 12 children …

https://sphoto.nasza-klasa.pl/8626671/7/other/std/ac937e11e0.jpeg