We hadn’t seen each other or talked for a while. I had gone outside Sunday afternoon, partly to get some air, but also to escape the assault of bad news about the coronavirus pandemic. But suddenly this friend dropped by for a visit in my backyard. The conversation was really welcome, but of course it was mostly about things closing, Canadians trying to get home or when this all might end. Eventually I asked how he and his family were doing.

“OK, mostly,” he said, and he then gingerly explained a member of his family had been diagnosed with cancer and was undergoing treatment.

“I’m sorry,” I said. But what I meant was, “Sorry that I let all this global chaos get in the way of caring about you and your family first.”

Clearly, I had expressed more worry about things over which I have no control, instead of caring about friends and neighbours whom I might actually be able to help. My myopia was a classic case of not seeing the forest for the trees.

So might that be said for a lot of us.

All week long, we’ve watched and listened on mainstream media and read in newspapers and online about the seemingly relentless march of the COVID-19 virus cases across Asia, Europe and North America – China counting thousands dead, Italian cities transformed to virtual ghost towns, stock markets spiralling to historic lows – all while we’ve watched medical scientists pleading with the public and politicians to pay attention to this unheard-of contagion, anti-virus hygiene, insufficient testing capability and the latest addition to our medical vocabulary “social distancing.”

“Stay two metres apart from others in public,” the scientists told us weeks ago. “Wash your hands frequently. Avoid handshakes, hugging and kissing.”

And equally painfully, we’ve watched politicians – presidents, prime ministers and premiers – weeks after they should have, finally line up at microphones in Washington, Ottawa and Toronto to announce states of emergency, money for equipment upgrades and funding for workers and businesses hit hard by the closing of bars, lounges, restaurants, schools (public and private), libraries, places of worship, cinemas, concert venues and other arts facilities … wherever people might potentially spread the virus.

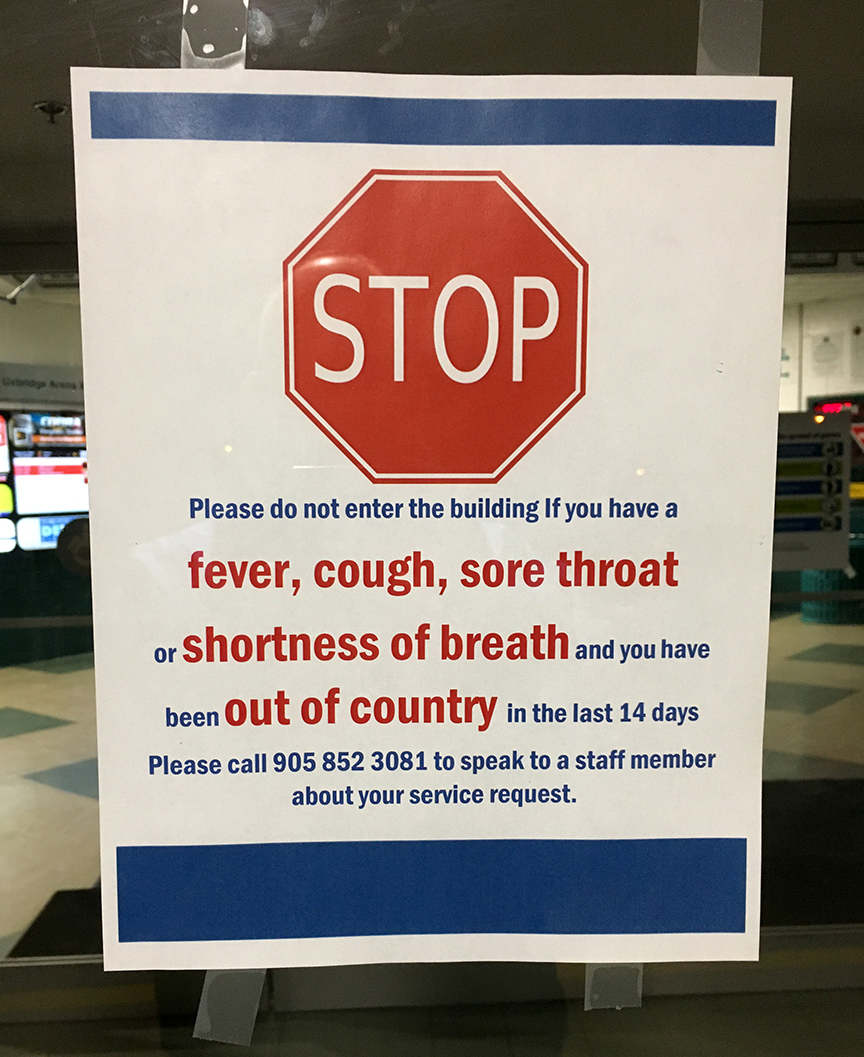

Lost in much of the posturing and scrambling where big decisions are made, I think, was the impact on local communites. The other night, I walked around downtown. The arena had big “STOP” warning signs on the front doors. The electric sign in front of the church at the corner, where scripture usually invited parishioners in, simply said “services cancelled.” The library, where many might find books and DVDs to fill self-isolation time at home, had only a small window for drop-off as a service. The Roxy had posted a “temporarily” closed sign.

And while I spotted a few clusters of folks in downtown restaurants, most eateries were dark and empty. I wondered whether any part of the belated grand plans of relief announced from the Prime Minister’s residence (where he and his family are in self-isolation) or from Queen’s Park will ever trickle down to our main street and its shuttered businesses and shutout staff.

What strikes me – especially in Canada – is that we saw this coming. Many of us went through the SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome) epidemic 17 years ago. This virulent viral respiratory outbreak (between November 2002 and July 2004) infected more than 8,000 people worldwide and killed 774 – 43 in Canada. And, despite equally uninspired political leadership then, public health scientists and medical staff managed to prevent even more catastrophic results.

My father, hospitalized in Scarborough Grace Hospital where the Canadian outbreak began, survived – not because of any bold steps from the provincial health minister – but thanks to public service workers such as Dr. Sheela Basrur. Most ran off panicking in all directions (including then Toronto Mayor Mel Lastman, who said to CNN, “Who is the WHO? They don’t know what they’re talking about.”)

Dr. Basrur, as Toronto’s first medical officer of health, appeared in the media repeatedly guiding the GTA through closures of public places, recommended public hygienic actions and gave Grace Hospital staff the means to contain the virus. My father was on the very floor of the outbreak and did not catch the virus! It’s sad that Dr. Basrur, who died of cancer in 2008, could not give us solace today.

I’m sure that – weeks ago – she’d have recommended that Ontarians stay calm, pay attention to public health directives about social distancing and avoid larger gatherings. Certainly, the gentle doctor would have told us to remain close to family and to look out for those vulnerable to respiratory illness.

Most important, I think she’d have told us to care for family members and to be the faithful friend and neighbour who stops, listens and offers help where possible – fighting the virus or just a sense of hopelessness, maybe the most debilitating side effect of all.