I never met John Birnie Dougall. But I came to know him this week, 79 years after his death. He spoke to me by way of his letters – letters he’d written as a Canadian merchant sailor keeping the supply of food, oil, munitions and hope flowing to Britain during the Second World War. As an example of his correspondence home, Dougall characterized the fate of Britain, in 1940, when it seemed Hitler’s U-boats would choke Britain’s shipping lanes to death:

“Even though England may be doomed,” he wrote in a letter to his mother Rachel, “each of us has fixed determination to do or die – a spirit that will not be beaten.”

Tomorrow, May 8, Canadians and Europeans will mark the actual date of Nazi Germany’s unconditional surrender. It’s the 75th anniversary of VE (Victory in Europe) Day. This past Sunday, the annual Battle of the Atlantic commemoration (normally held at Point Pleasant Park in Halifax) took place online.

For those who don’t know, that siege at sea proved to be Canada’s longest military engagement of WWII, fought from the outbreak of the war in September 1939 right up to May 1945. Almost 2,000 members of the Royal Canadian Navy died in battles across the North Atlantic, as well as 750 Canadian airmen. Not often acknowledged in this crucial campaign, however, 1,451 merchant sailors “carrying the lifeblood of the U.K.” died in the Battle of the Atlantic too. John Birnie Dougall was one of them.

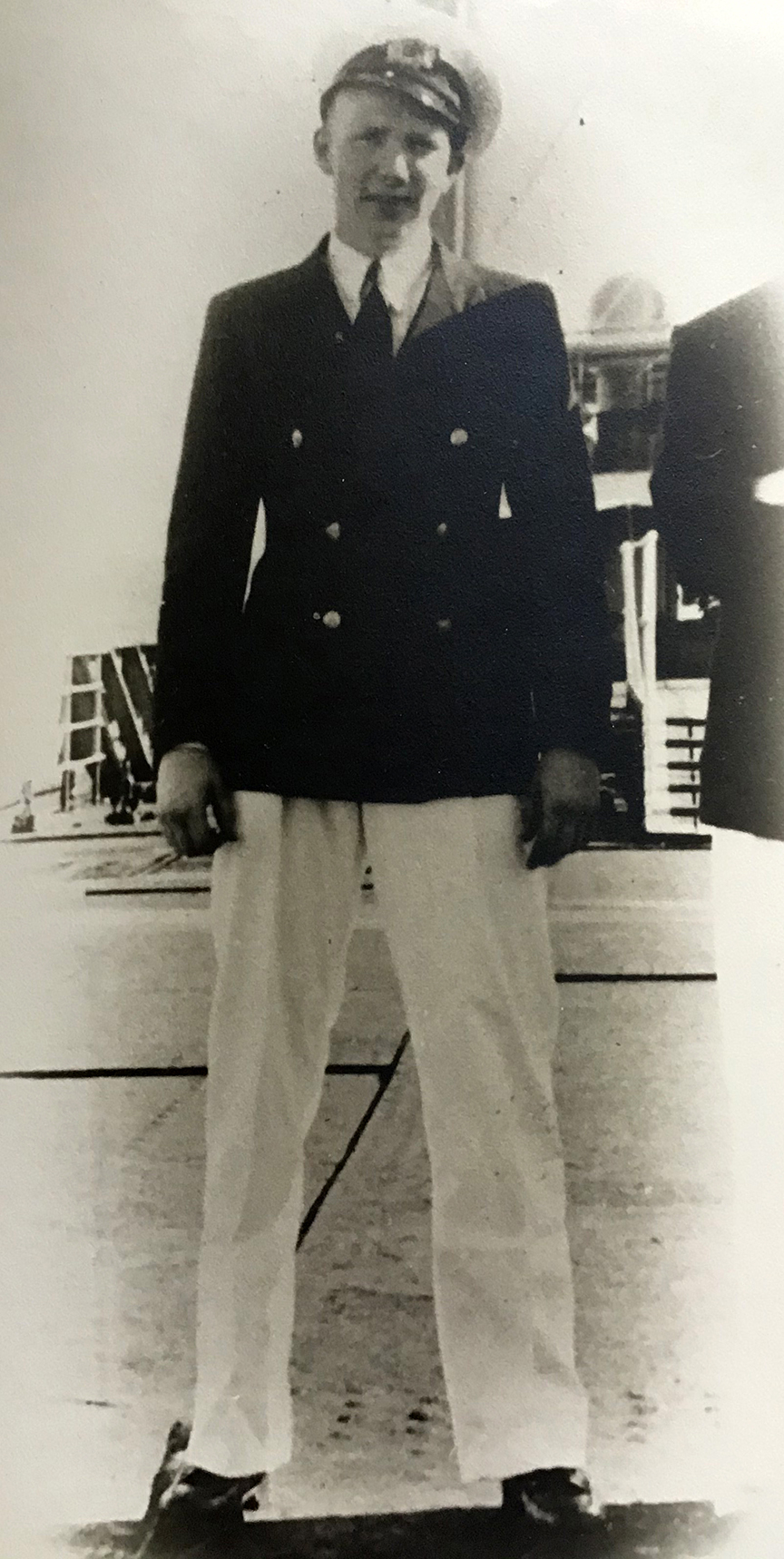

By coincidence, Dougall’s niece, Jane Hutchison, whom I met at a Canadian Club talk in Halton a while ago, mailed me correspondence that her uncle kept up throughout his wartime service – first as an apprentice aboard the British oil tanker San Felix in 1940, and then in 1941 as a third mate serving on the Scottish freighter Gretavale.

Most merchant shipping companies knew the high risk of U-boat attack between North America and Britain, and that, according the RCN Admiral Leonard Murray “up to 25 per cent of (sailors) would not arrive in the U.K.”

Age 18 and barely out of high school in Cornwall, Ont., John enlisted the help of family in Scotland to get him hired aboard merchant tankers whose home port was London, England. From the British Isles, the tankers (often armed with naval guns) sailed to Venezuela to load thousands of tons of oil bound for British industry.

Then, the tankers joined convoys at Halifax or Sydney, Nova Scotia, running the gauntlet of winter gales, fog and icebergs, not to mention wolf packs of German U-boats across the North Atlantic back to Britain. As an apprentice, John served long hours on the open sea, training and studying to acquire his certification “ticket,” while taking his turn at the helm of the ship.

“Just taken over the wheel,” he wrote his mother in May 1940, “when a station alarm went off. So, to the gun platforms we scrambled and eyed along the gun barrels for (U-boat) periscopes. One of our escorts let go depth charges and even three miles away our ship nearly shuddered to pieces with the vibration.”

Beyond his own safety and off-shift time studying logarithms, trigonometry, navigation and seamanship for his third mate’s certification – during three years at sea – young Dougall appeared to shoulder much responsibility for his family back in Cornwall.

Sending a portion of his $45 monthly wage home, supporting his mother through ill health, and keeping his younger brother in line, meant a regular flow of letters home from all of his ports-of-call. When his brother graduated with honours, John challenged him to go to college, because, “it’s what you have in your head that counts in this world.”

In 1941, John Dougall completed exams for his mate’s papers and took a position with a new shipping employer aboard the freighter Gretavale. His crossing from North America early that November would be his first as third mate, during one of the darkest periods of the Battle of the Atlantic.

“If I should go down, don’t you fret, for I shall be angry either above or below,” he wrote his mother. “After all, the sea is my life. If I have to be splashing about in it, it is the way I would want to go – living the spirit of the sea. With that off my chest, cheerio ’til you hear from me again. Yours… J. Dougall.”

The family never did hear from John again.

On Nov. 3, in an eastbound convoy for the U.K., the Gretavale – loaded with tons of steel and trucks for Britain – was torpedoed and sunk off Newfoundland. All but a handful of the 47 crew were lost. So, while this week many are remembering the liberation of the Netherlands and VE Days celebrations across Canada, I’ll note those commemorations too.

But I’ll also thank Jane Hutchison for letting me meet her uncle John Dougall through his letters. He and his merchant navy comrades also secured the victory at sea.

Thanks Ted, for pointing out to me your post based on John Dougall’s letters.

You wrote a really interesting article and I look forward to learning more about the Battle of the Atlantic in your next book. I can understand why Jane Hutchison would be so pleased to see her uncle’s story in print.

Take care, Barb