Imagine a curfew keeping you inside your home. You can. Imagine quarantine as if it were imprisonment. You can. Then, imagine coming up with a unique way to deal with your isolation by turning to one of your life skills. I imagine that you can do that too.

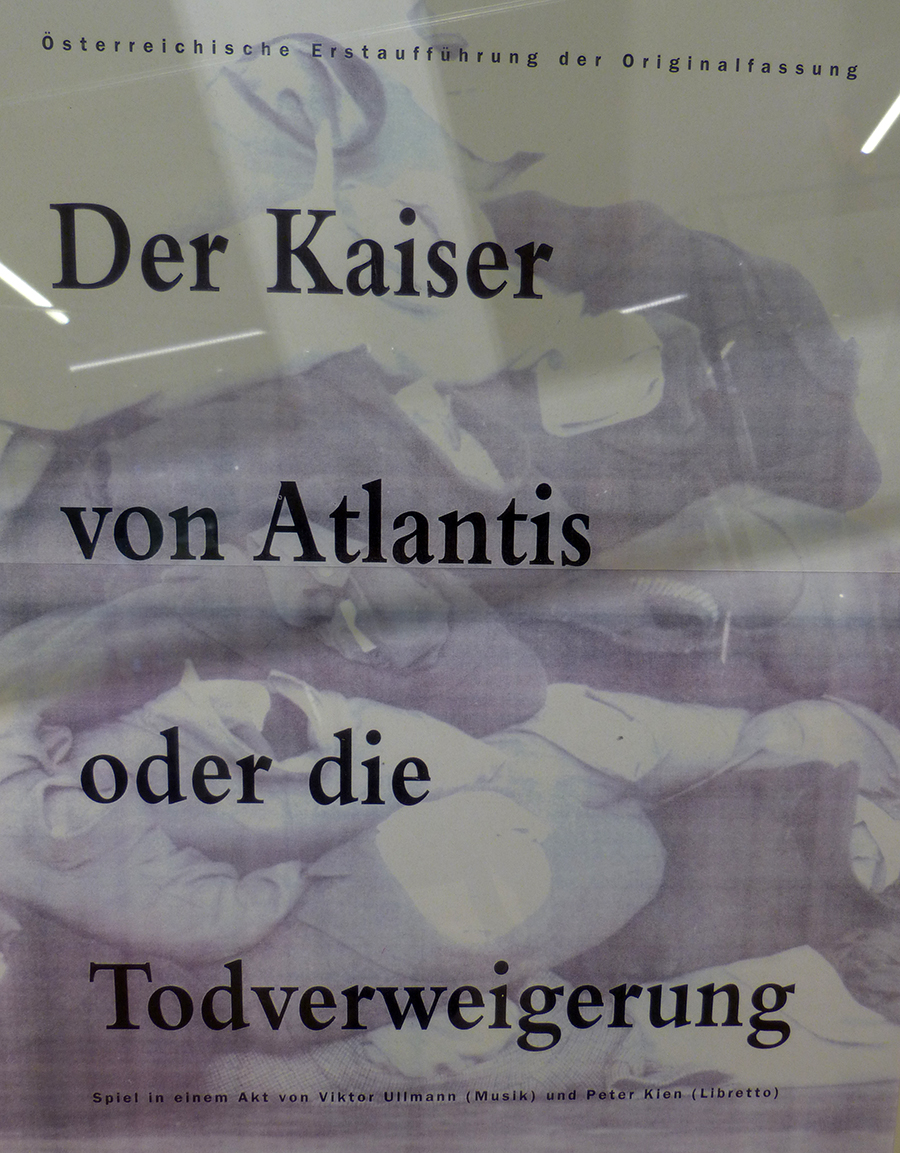

That’s what Victor Ullmann did, in 1942. Imprisoned at a place called Terezin, a concentration camp in Nazi-occupied Bohemia, Ullmann, a music composer by profession, wrote an opera inside the prison depicting his predicament. It was called The Emperor of Atlantis.

“It’s a (musical) parable about a mad, murderous ruler,” wrote a reviewer years later, “who proclaims universal war.”

Born in Vienna, trained at the Second Viennese school, in Austria, and at the apex of his artistic abilities, in September 1942, Ullmann was deported to Terezin because he was also Jewish. Undeterred, the 44-year-old artist secretly composed songs, choir repertory, and charts for string quartets and piano sonatas inside the concentration camp.

And though the camp’s SS Kommandantur never allowed its performance (partly because the opera appeared to satirize Hitler), Ullmann’s Emperor was smuggled out of Terezin in 1944, just as its composer was transported to the gas chambers at Auschwitz.

The opera outlived the Nazis, however, and was staged first in Amsterdam in 1975, then in the U.S. and U.K. in 1977 and 1985 respectively.

I offer Viktor Ullmann’s courageous story neither to exploit the tragedy of his murder nor to insult his memory with this comparison, but it strikes me that in spite of the hardships of widespread isolation – whether a manmade calamity or one born of natural causes – much greatness can come from within catastrophic events.

Pablo Picasso’s depiction of the fascist bombardment of the Basque town of Guernica in 1937, further illustrates the point. The twisted, dismembered bodies of men, women and children and the shrieking of a horse amid the chaos in the streets, make Picasso’s Guernica stand out as remarkable symbol of its time.

The newly elected Republican government had asked the artist to create a painting for the Spanish Pavilion at the 1937 Paris World’s Fair. But history overtook Picasso as the fascist forces of Francisco Franco (supported by Hitler’s Luftwaffe) obliterated the pro-Republican northern village killing or wounding 1,600 civilians.

“I clearly express my abhorrence of the military caste which has sunk Spain into an ocean of pain and death,” Picasso explained of his 20th century masterpiece.

In his time, William Shakespeare coped with conditions not unlike COVID-19. The Bard lived in the late 16th century when all manner of pestilence ravaged England. Weeks after baby William was baptized in Stratford-upon-Avon, in 1564, the church registry recorded, hic incepit pestis (here begins the plague).

Some suggest Shakespeare penned King Lear in the early 1600s, in the middle of another plague. We know this because instead of opening the play at public theatres, Shakespeare premiered it in front of the monarchy at the Palace of Whitehall. Add to that, Lear even curses his daughter with:

“Vengeance, plague, death, confusion,” and calls her down as “a plague-sore.” It’s sad for all of us, that the current coronavirus has felled Canada’s 2020 Stratford Festival season.

About five years ago, I travelled to Washington, D.C., and on a warm fall day was invited to visit a newly inaugurated park near the Pentagon. As I approached northwest side of the iconic building, that day, a woman in a red Polo shirt with her name “Laurie Laychak” and her title “Volunteer” embroidered on it stood waiting. I introduced myself and asked if she would show me around the recently inaugurated park.

“This is the Pentagon Memorial Park,” Laychak said. “This is where American Airlines Flight 77 struck the building on Sept. 11, 2001.”

“Of course, the fourth hijacked jet during the 9/11 terrorist attacks,” I said. “And what’s your connection?”

“My husband David Laychak was literally at ground zero, where the plane hit the Pentagon,” she explained, and she led me along inlaid granite walkways, past reflective ponds and Crape Myrtle trees to one of the 184 stainless steel memorial benches where her husband’s name was inscribed.

Laurie and I sat for an hour as she explained the aftermath of 9/11 – grieving a lost husband and helping their two children to recover. As painful as this place was for her, Laurie Laychak made her volunteer work a personal commitment to his memory and therapy for feeling so alone.

“I feel compelled to make sure visitors know these people were not numbers, but actual lives,” she said.

A final point: In 1995, Viktor Ullmann’s clandestine opera, The Emperor of Atlantis, made its triumphant return to Terezin concentration camp. It was performed inside the very prison where Ullmann had composed it. In spite of Hitler, the Holocaust and his murder at Auschwitz, Ullman’s art had superseded curfew, imprisonment and isolation to showcase his brilliance forever.