It stands about three feet tall. It looks like a stone pedestal, but it has no statue on it. It’s not located in an obvious public square or along a busy thoroughfare. It’s a war memorial, but it doesn’t glorify a victory, nor mourn a defeat, even though for Canadians it signifies tremendous loss.

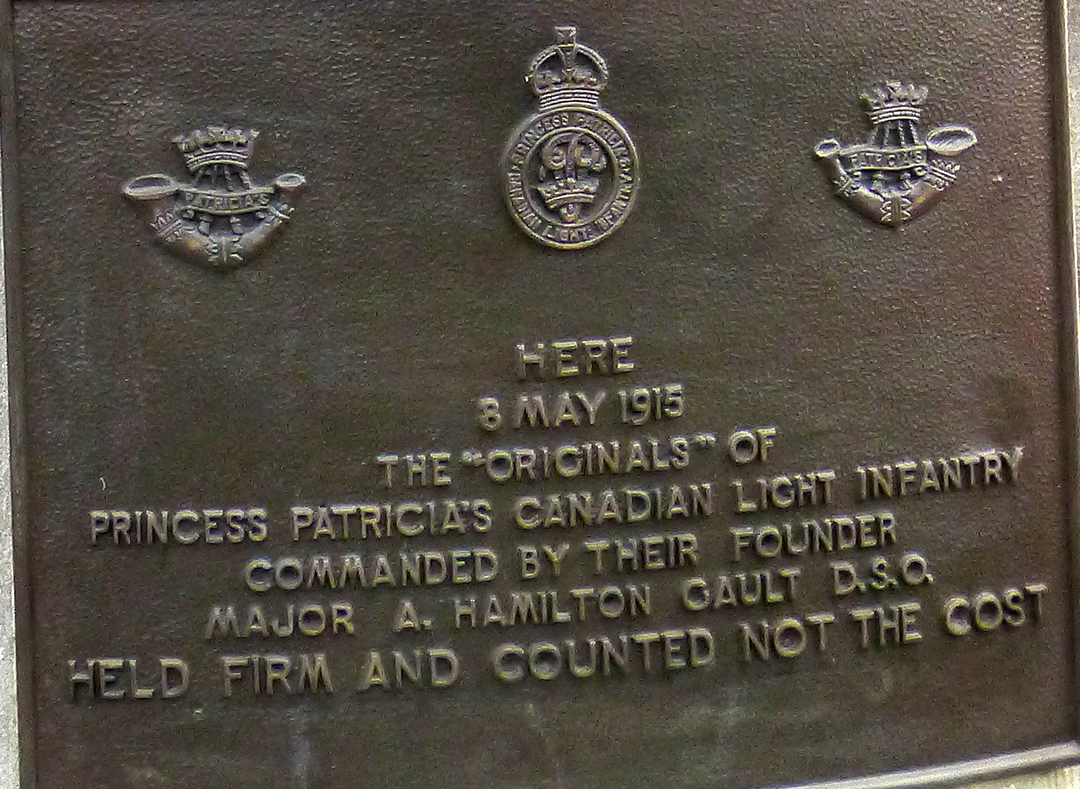

When I’ve taken fellow Canadians there, I’ve always been struck by its simplicity, modesty and basic message. Its only identification is a brass plaque across one side of the pedestal with an inscription:

“Here, 8 May 1915, the ‘Originals’ of Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry, commanded by their founder Maj. A. Hamilton Gault, DSO, held firm and counted not the cost,” is all it says.

The first time I went looking for this war memorial, eight years ago, I almost missed it. The battlefield bus tour I was leading through Belgium had PPCLI veterans along, and they’d mentioned they’d like to see this memorial. They said the “Originals” cairn was kind of a touchstone location for them, the place where PPCLI units suffered their first-ever casualties in the Great War.

Suddenly, I spotted a sign directing us up a country road. At the end of it, I expected maybe an arrangement of flags or a marble sculpture, possibly a statue of a Canadian soldier or something. But no. It was just this modest circular stone with a written tribute to the Great War’s very first PPCLI war dead.

I’ve thought a lot about that “Originals” monument lately, as demonstrators around the world have reacted to the murder of George Floyd and knocked down or defaced statues they believe signify oppression and racism.

Protestors quite rightly are angry with edifices to men who (at the time) seemed great leaders, but who also kept others in bondage. Statues once raised to honour the life of Christopher Columbus have been toppled in Richmond, Virginia, and St. Paul, Minnesota – the one in Boston was beheaded – over Columbus’s treatment of indigenous people. In Britain, protestors have brought down statues commemorating Edward Colston and Robert Milligan, both former slavers.

And in the U.S., the statues of former leaders of the Confederacy in the U.S. Civil War have fallen like ten pins – Jefferson Davis, Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson in Richmond; Albert Pike in Washington; Dick Dowling in Houston; and Charles Linn in Birmingham. They stood and fought for the preservation of the Southern institution of slavery. Historical individuals once revered, have suddenly been revealed.

Hurray for that! Nowhere should those who would trample on the rights of others, or worse, murder them through a warped sense of superiority. But has it occurred to anybody, that in eliminating all trace of these figures, we’re erasing that history? Have those eager to topple statues and dump them in the river considered how to explain what those fallen heroes and icons did wrong?

Sure, wipe the slate clean of their celebrity and evil ways, but in their place we need to show next generations how they did what they did, and why they rose to fame in spite of it, and then how their infamy survived in a sculpted edifice. Erase the evil, but show the evidence.

Not so long ago, I tripped across an episode of the iconic BBC TV series, World at War. It told the wartime tale of Oradour-sur-Glane, a small village in central France that paid the supreme price for its resistance to Nazi occupation from 1940 to 1944. The excerpt was narrated by none other than Sir Laurence Olivier. The segment walks the viewer along a deserted street.

“Down this road, on a summer day in 1944,” Olivier explains, “the soldiers came. They stayed only a few hours. When they had gone, the community which had lived for a thousand years, was dead.”

He relates how the civilian men in Oradour were led to garages and barns and shot by the German troops, who then led the women and children to the Catholic church, where they too were killed. With the dignity and empathy that only Olivier could bestow on such a narration, he finishes by saying:

“They never rebuilt Oradour. Its ruins remain as a memorial.”

Even today, the abandoned village stands as a tribute to the 642 killed on June 10, 1944, as a reprisal for the Allied landings in Normandy four days before. I’d venture to say that nobody who visits that town or views that segment of World at War, ever forgets what happened there. Or why.

It’s the same as that simple marker in Belgium I’ve visited with battlefield travellers. The “Originals” monument to the fallen of PPCLI troops in 1915 offers a remembrance of what happened there. It acknowledges the senseless loss. It does what any historic monument should do – it describes the travesty, displays the context and inspires all who visit to draw the lesson for themselves.

It’s the same as that simple marker in Belgium I’ve visited with battlefield travellers. The “Originals” monument to the fallen of PPCLI troops in 1915 offers a remembrance of what happened there. It acknowledges the senseless loss. It does what any historic monument should do – it describes the travesty, displays the context and inspires all who visit to draw the lesson for themselves.