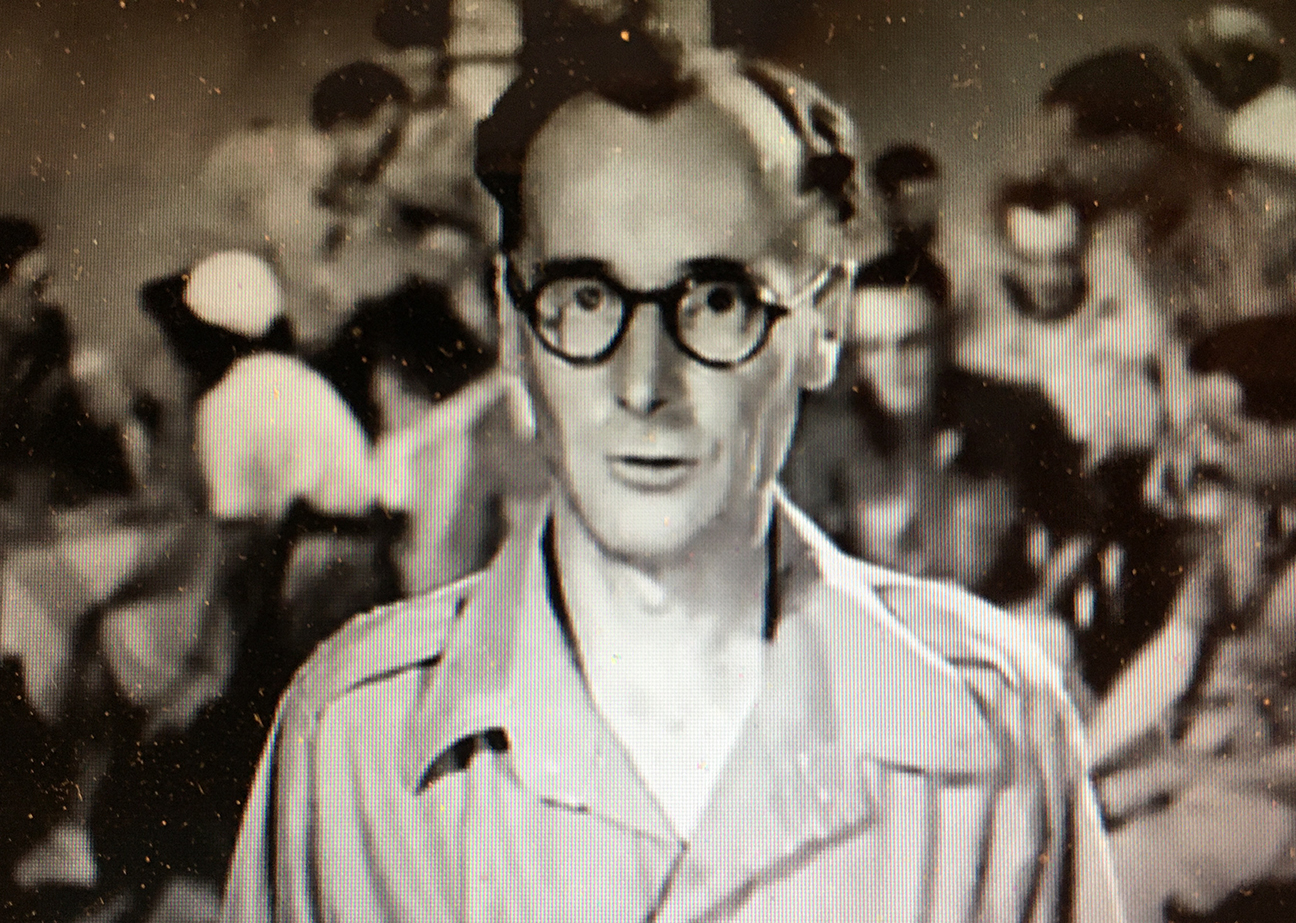

A soldier with circular spectacles, corporal’s stripes on his sleeve and khaki shorts on, walks toward a stationary camera. He smiles as he acknowledges the commotion around him. Glasses clink. There’s a general hubbub of voices in friendly conversation. He’s in a military pub – circa 1940s – and stops in a kind of selfie-framing attitude and speaks right to camera.

“Hello, Joy. How’s this for a wartime miracle?” he begins. “And a novel way of saying, ‘I love you.’”

The clatter continues behind him, as the corporal admits he probably looks a bit different to his lady love, Joy.

“How ever I look,” he continues, “I’m still the same in heart and mind and longings, and full of appreciation of your own grand affection.”

The corporal is one of the hundreds of thousands of British soldiers in the finals days of fighting the Japanese Imperial Army in Burma, at the end of the Second World War. And his on-camera testament of affection to Joy is one of a string of greetings on a piece of black-and-white motion picture film discovered recently during a renovation at the town hall in Manchester, England.

These three minutes of film, without a single edit, present young soldiers, each stepping up to the lens of the camera one after another to pass along wishes to loved ones back home in England.

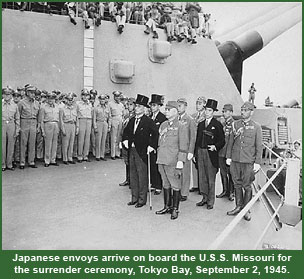

Tomorrow marks the 75th anniversary of the end of the Second World War. In Europe, the Italian fascists and Hitler’s armies had capitulated on VE-Day, May 8, 1945. Three months later the U.S. Army Air Force dropped atomic weapons on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, in Japan, on August 6 and 9 respectively.

Then, on August 14, 1945, USAAF B-29s bombed Tokyo with thousands of leaflets, calling for Japan to surrender. Emperor Hirohito announced the war was over. (Japan surrendered officially aboard the USS Missouri, in Tokyo Bay, on Sept. 2, 1945.)

It would still be many months before British troops in Asia were repatriated. So, as a morale booster, BBC presenter, Maj. Jack Frost, came up with the idea of using mainstream media – a motion-picture camera and a full magazine of film – to let the men at the front pass along their thoughts in an unedited, stream-of-consciousness kind of wartime movie postcard.

The film was posted on YouTube by British journalist Sophie Atkinson. After the corporal expressed his love to Joy, he handed it off saying, “Here’s Bob to say a few words to Mrs. Martin…”

“This is indeed a great pleasure to be able to speak to you in this manner,” Bob Martin said. All quite formal in his articulation, but a bit tongue-tied, he finishes with a traditional, “God bless you all. Now, here’s Frank with a message for those at home…”

Another bespectacled soldier, this one taller and older than the others, greets wife and brother and assures them all, “I’m feeling fine and having a good time out here.”

In truth, British troops in what was then Ceylon and Burma, as well as Malaya and Hong Kong – defending British commonwealth populations in south-east Asia – not only endured tough jungle fighting, but, as a consequence, tropical diseases, such as malaria, pellagra and dysentery.

Most spent six years there, either fighting an entrenched enemy or surviving in Japanese POW camps. But the soldiers on the film, while rather thin and worn, still smiled for the folks at home.

“Hello, Ivy, darling,” began a soldier named Eddie. “I trust that you and Terry are in the best of health. I am O.K., so don’t worry about me. Thank your mother and father for the nice parcel they sent me.” (Notice he didn’t say ‘mum and dad’; he knew the camera was running). Then, he offered one of those rare wartime coincidences you only hear about, but it really happened.

“Who do you think I heard from the other day?” Eddie continued. “My brother, Bert! I hope in a few days’ time to be seeing him.”

One of the last of the troops to step forward to Maj. Frost’s camera was the youngest. Cpl. Marshall saunters to his spot in front of the lens, film still running, and speaks.

“Hello, Dad,” Marshall begins. “I hope you and the family are doing all right. You can see for yourself how fit I am. Can’t say very much to you.” Then, he lifts his empty glass as if he were in a local pub, and finishes, “Guess I’ll just go and get the old glass filled up again.”

So, the next time any Millennials, or Baby Boomers, suggest they invented social media, remember Maj. Jack Frost’s film clip from Burma from the 1940s, when soldiers behind the front lines 75 years ago came up with a selfie for the folks at home. LOL.