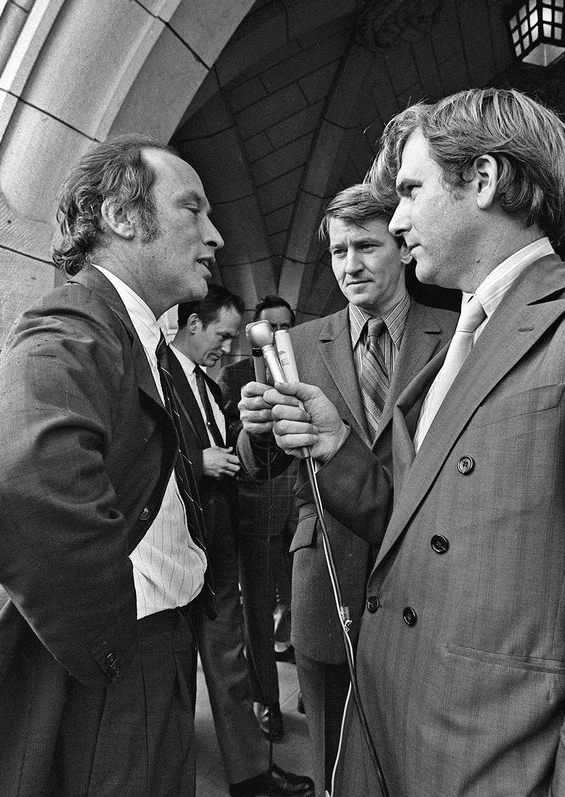

It was a moment on live television – something considered rare then. The Prime Minister, Justin’s father, moved up the steps to his office on Parliament Hill. Reporters converged and questioned, one of them, Tim Ralphe, more aggressively than the rest. He poked his microphone at Pierre Trudeau and pressed the concern of many in Canada at that moment.

“Sir, what is it with all these men with guns around?” he asked.

The day before, Oct. 12, Trudeau had called for the Canadian Armed Forces to deploy armed troops to protect high-profile locations and individuals in Ottawa and Quebec City.

“Well, there are a lot of bleeding hearts around who just don’t like to see people in helmets and guns,” Trudeau said. “But it is more important to keep law and order in society than to be worried about weak-kneed people.”

Ralphe, later in the unique 10-minute exchange on the Hill, asked just how far the Prime Minister was prepared to go.

“Just watch me,” he said.

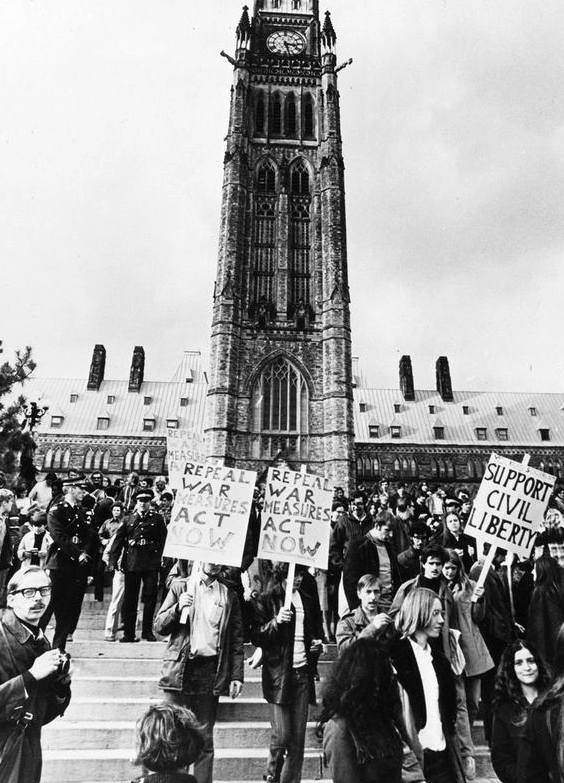

It’s 50 years ago this week that historic tête-à-tête occurred in Ottawa, 50 years since those soldiers took up positions in front of Parliament and the National Assembly, 50 years since the October Crisis in 1970.

That was the year members of the Front de Libération du Québec (FLQ) kidnapped James Cross, a British trade commissioner, in Montreal. They then demanded money, safe passage to Cuba, the release of 23 detained FLQ members (some previously convicted of bombings, holdups, manslaughter or murder) and the broadcast of the group’s manifesto in return for Cross’s release. I remember the voice of Radio-Canada announcer Gaetan Montreuil reading the manifesto over the CBC.

“We will always be the assiduous servants and the boot-lickers of the (English-speaking) big shots,” the document stated.

Minutes after the Quebec government of Robert Bourassa refused the rest of the Front’s demands, on Oct. 10, another FLQ cell kidnapped Pierre Laporte, the vice-premier and labour minister in Quebec. Overnight, this distant and disorganized protest group seemed immediate and threatening. That’s when the Prime Minister deployed the Army and positioned them on Parliament Hill and in front of the Quebec National Assembly.

I recall years later interviewing now retired Sen. Romeo Dallaire. I asked him about his most difficult assignment as a soldier. I expected him to offer his thoughts about his mission in Rwanda during the genocide in April 1994.

“It was the time of the October Crisis,” he said. “My unit was guarding the Quebec National Assembly. I didn’t know if one minute all would be calm, and the next I might be levelling my weapon at a neighbour or relative.”

We speak today about palpable fear – fear brought on in our lifetimes by the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962, the terrorist attacks in the U.S. on Sept. 11, 2001, and in 2020 by the rampant spread, lockdowns and now resurgence of COVID-19. But four days after Pierre Trudeau delivered his “Just watch me” response to Ralphe, the PM invoked the War Measures Act (WMA), suspending all public civil liberties. Then, on Oct. 17, Pierre Laporte was found murdered. Trudeau promised “unceasing pursuit of those responsible.”

Throughout the tense days of the kidnapping and murder of Laporte, I went about my second-year studies at Ryerson. To gain a bit more experience (and a few extra dollars) I hosted an all-night music and talk show on Ryerson’s broadcast outlet – CJRT-FM (later Jazz FM 91).

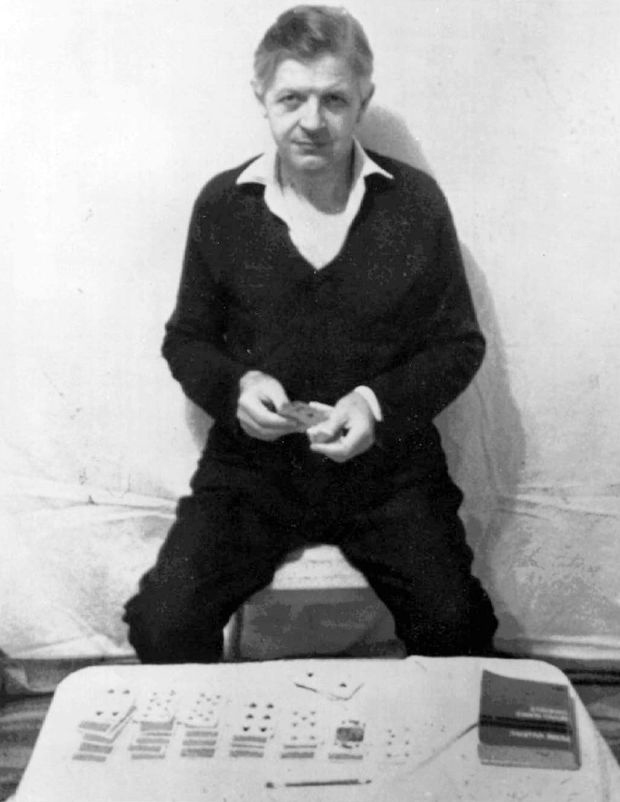

As the Friday and Saturday night show host, I had a pretty high opinion of myself as well as my music and interviewing skills. One night at a gathering, I met a man, one of some 497 who’d been arrested under the WMA. It seemed a natural reaction to invite him to my show and query him on-air live about Quebec under the WMA.

“Tonight, I have an exclusive,” I remember telling my audience.

That audience included a number of friends and media colleagues who expressed tangible, visible panic over the events in Quebec in 1970. It turned out by exploring the kidnappings and arrests of civilians on the air, however, that I was in effect violating the WMA. It clearly stipulated that outside of newscasts, interviewing and commentary on the crisis was illegal. What I didn’t realize was that the WMA effectively removed all civil rights – free speech, rights of assembly and the freedom of the media.

In the days that followed the climax of the crisis, arrests were made (Laporte’s killers tried and imprisoned), James Cross was released unharmed (his captors exiled to Cuba), and the WMA lapsed on April 30, 1971. And the fear faded with memory.

But I think I learned a vital lesson in the October Crisis 50 years ago – rights and privileges are only as strong as those who enshrine them, abide by them and protect them.