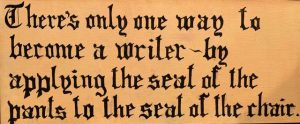

The sign always hung in my father’s office, right over the spot where he worked. That happened to be just above his typewriter (in a time before computers) where Dad pumped out many millions of words in a life-long writing career. But Dad had installed this sign over his work space for those days at his office in the basement of our house when maybe the spirit to actually put fingers on keys occasionally eluded him or when he periodically felt unmotivated.

“There’s only one way to become a writer,” the sign read, “by applying the seat of the pants to the seat of the chair.”

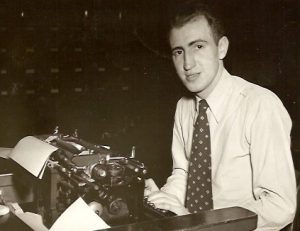

My father, Alex Barris, wrote probably a thousand radio, television and movie scripts, hundreds of columns for newspapers and periodicals, scores of screenplays and at least half a dozen books at that typewriter in his basement office. And I frankly doubt that he ever needed encouragement, coaxing or cajoling to put the seat of his pants on the seat of his chair.

My father was self-motivated. He started to work as a freelance writer beginning in the 1950s (when most people couldn’t spell “freelance” much less do it). Today’s parlance for “freelancing” is working in the “gig economy” or among those working from home during the pandemic, “remote work.”

My father was self-motivated. He started to work as a freelance writer beginning in the 1950s (when most people couldn’t spell “freelance” much less do it). Today’s parlance for “freelancing” is working in the “gig economy” or among those working from home during the pandemic, “remote work.”

At last count, according to an Angus Reid survey (published by H&R Block) in April 2022, about 13 per cent of Canadians reported working in the gig economy. The survey defined it as freelance or contract work in such work as air B&B, Uber, dog walking, couriers and commission-only sales to name a few categories.

Particularly since the pandemic lockdowns of 2020 and 2021, nearly a million other Canadians surveyed joined the freelance workforce because they were forced to work from home. Nearly 20 per cent of Canadians told the survey they’d never worked in the gig economy but would try it in order to make ends meet. Finally, the survey revealed more than half of the working population had no interest in the world of freelance whatsoever.

The survey offered some of the pros and cons of working for oneself. On the upside, it listed such positives as being able to pocket cash made immediately on payment (rather than waiting for a corporation to make deductions, file and release funds). It also recognized potential tax advantages; with more declared income, the survey noted, gig workers have more room to contribute to RRSPs and other tax shelters.

On the downside, freelance service workers face the difficult task of keeping track of tips, because they’re taxable income. And if gig earnings exceed $30,000 a year, the freelancer has to register for a GST or HST number. (As a freelancer for nearly 50 years, I truly resented when Brian Mulroney introduced the GST in 1991, making me a part-time accountant submitting quarterly goods and services reports.)

But all that is the tangible baggage that freelancers carry. I think the Angus Reid surveyors missed the essence of a freelance/gig/remote work-life existence. First the freedom. Depending on the nature of the work commitments, freelancers can specialize or generalize their skill sets. As long as they meet deadlines (set by themselves or their clients) they can schedule their labour whenever it suits.

Even at my busiest times, as a freelancer, I managed to balance the demands of writing commitments with the pleasures of attending family moments. I attended school concerts, plays and graduations where some of my friends in staff positions couldn’t. And most liberating of all, I’ve juggled the writing that had to be done, with the writing I wanted to do.

Of course, the elephant in the room now – with the end of stay-at-home pandemic restrictions – is that many businesses forced to allow their employees to work from home are calling them back to the office. Large corporations (particularly those with empty office towers such as financial institutions, life insurance companies and department stores) want those downtown spaces re-occupied.

Particularly now, with summer officially over, some of the big banks and law firms have mandated office attendance. They say it’s all about the role that teamwork and collaboration plays in productivity and the bottom line. But now more than ever, former office workers who’ve experienced the benefits (and pleasures) of a work-at-home alternative are pushing back. Some business observers call it “a collision course” between remote work and the culture of 9 to 5.

My father’s basement office space is long gone. So too is the sign that hung over his typewriter. But among those members of my family who’ve cultivated freelance lives, the seat of the pants continues to hit the seat of the chair and get the work done.

I actually still have the sign. I painted it and framed it for Dad after he mentioned the quote. He claimed it was said originally by Sinclair Lewis, but checking in with Google, I see Lewis actually credited Mary Heaton Vorse as the person who gave that advice. For what it’s worth.