I had just finished one of my anti-technology rants. I’d complained about something my computer had lost. I was angry that our television service provider had updated all of our access to programming such that I needed an electronics degree just to tune in the news. And I hated the way some of the on-air newscasters mispronounced names and places. My wife patiently waited for me to take a breath.

“Is there anything that made you happy today?” she asked.

And I smiled sheepishly back at her. Then, apologized. We agreed that anger has become prevalent. People feel perfectly comfortable raging – whether it’s at their TVs, other drivers on the road, public servants, flight attendants, health-care workers, restaurant servers, and maybe even their own family members. In the course of apologizing to my wife, I noted that anger seems to be a sign of the times. And it’s a bad sign.

Among the first places I noticed this unbridled rage was a year or so ago – with the COVID pandemic between waves and vaccinations beginning to reduce deaths – when the major airlines began opening up flights to travel again.

Suddenly, people who’d been masking, isolating, and tracing contacts for two years in their homes had become passengers in an enclosed space for hours with others who might not agree with them politically. Circumstances provoked some travellers to unravel.

A New York Times feature writer quoted flight attendants having to duct-tape a drunken passenger after he physically and verbally assaulted them.

“What really hurts are people who won’t even look you in the eye,” a flight attendant told writer Tracey Rychter. “I don’t even feel human anymore.”

The Times’ reporters ran a series of investigations about people’s attitudes at this stage of post-pandemic life. They revealed startling reactions expressed in grocery stores, government service lines, gas stations and restaurants. In one case, at a café in the eastern U.S., a group of diners grew so furious at the long wait for food that they demanded the meals be boxed up; then they dumped all the orders, uneaten, into the garbage.

The waiting staff was so traumatized, the owner gave them “a day of kindness” break. Much of this comes from society transitioning back to regular consuming habits and expectations when the original delivery system is broken. People want things to be back the way they were, right now, or else!

I trace a lot of this sentiment to the polarization of North American politics. Where once our legislatures and congresses housed civilized discourse on policy and the evolution of law, today we see and hear nothing but name-calling and rancor.

The rise of populism and nationalism in the name of Trump Republicanism has done nothing but play on anger. When Trump accepted the Republican nomination for president, he hailed his audience of angry yet noble sufferers as “the forgotten, the downtrodden, the discarded, and the subjugated,” he said, then shouted, “I am your voice!”

Capitalizing on anger got him elected, but his resulting presidency had few successes, constant staff turnover, spiraling government debt, trade wars, government shutdowns and, oh yes, the Jan. 6 insurrection on Capitol Hill.

I noted the assessment from Thornhill, Ont., MP Melissa Lantsman, who described Pierre Poilievre’s strategy for winning the Conservative leadership like “taking anger … and making sure that we capture it a bottle.”

Bottling anger, however, isn’t a panacea. Calgary political scientist Duane Bratt pointed out earlier this year that a savvy politician can leverage anger and channel it during a political campaign and even win a victory on election night. But he asks, “What about the day after? While anger is a great strategic tool for winning elections, it is a poor strategy for governing.”

He suggests that anger leads to short-term fixes, bad promises, inappropriate choices, the creation of enemies and ultimately more anger.

Does anybody recall Howard Beale? If a man in a wrinkled trench coat, waving his arms around like a madman in front of a TV newsroom camera comes to mind, you remember the 1976 movie Network.

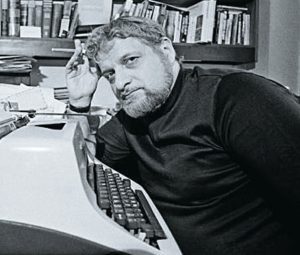

According to its creator, screenplay writer Paddy Chayefsky, newscaster Beale (played brilliantly by Peter Finch), crystallizes the anger and powerlessness felt by people with no recourse, no options, no plan. He is anger without a clear target. “I’m mad as hell and I’m not going to take this anymore,” he shouts.

By the way, in answer to my wife’s question – did anything make you happy today – absolutely. When I walked my grandsons to school that morning, they told me about the view from the top of the Ferris wheel at the fair and how great the cotton candy tasted. You see, anger can be defused.