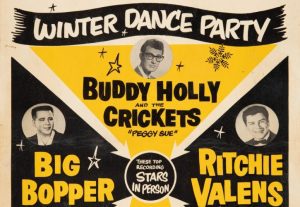

It happened sixty-four years ago tonight. Their tour, “the Winter Dance Party,” had just finished a show at the Surf Ballroom in Clear Lake, Iowa. But several of the rock ’n’ roll performers were suffering under winter conditions on the road in the U.S. Midwest.

It happened sixty-four years ago tonight. Their tour, “the Winter Dance Party,” had just finished a show at the Surf Ballroom in Clear Lake, Iowa. But several of the rock ’n’ roll performers were suffering under winter conditions on the road in the U.S. Midwest.

Singer J.P. Richardson, a.k.a. Big Bopper, had the flu. Drummer Carl Bunch had frostbite in his feet from travelling on a frigid tour bus for 10 days. Bass guitar player Waylon Jennings was suffering too. A long bus ride in the cold to Moorhead, Minn., lay ahead.

“Buddy (Holly) told me he had chartered a plane for me and him and (guitarist) Tommy Allsup,” Jennings said in a YouTube interview 10 years ago. “But the Big Bopper had the flu real bad. He asked if he could have my seat on the plane. I said OK.”

Meanwhile, Tommy Allsup and Ritchie Valens met backstage, Allsup explained. “And Ritchie said come on (Tommy), let me fly. So, I pulled a half-dollar coin out of my pocket and flipped it. He called ‘heads’ and it came up ‘heads.’”

So, but for a swapped seat and a coin toss three of the biggest names in pop music in 1959 – Valens, Big Bopper and Buddy Holly – were lost. Most agree that Charles Hardin Holly blazed a unique trail in the early days of rock ’n’ roll. The tall, slim, bespectacled boy from Lubbock, Texas, began as a country singer in the summer of 1957, but edged into rock with songs such as That’ll Be The Day, Maybe Baby (with his original band the Crickets) Oh Boy and probably his classic Peggy Sue.

Because I had always been fascinated by “the Winter Dance Party” tour story and at the time produced a daily radio current affairs program in Saskatoon, as the 20th anniversary approached, I chased down Don McLean; he’d immortalized Holly’s death with the lyrics “the day the music died” in his song American Pie in 1971.

But I was even more fortunate to find Marie Elena Santiago Holly, Buddy’s widow. She consented to an interview and told me how the two met when she worked as a receptionist in a music publishing office in New York.

“I didn’t even know who he was, even though I was sending out his records,” she admitted in our interview. “It was a mutual admiration society right away. I just fell, like boom. He fell the same way.” She went on to say that he was the first man she’d ever dated. It proved a memorable outing, because Holly proposed to her.

After they married, Holly split up with his band, the Crickets, chose to perform solo and shared side-musicians with Ritchie Valens and Big Bopper. Then, came “the Winter Dance Party” tour. Maria wanted to join Buddy. “But I was pregnant and stayed home. It was an awful tour. People were getting sick. The bus kept breaking down.

“When they reached the Surf Ballroom (in Clear Lake),” she told reporter Bettina Dizon in 2021, “he said it was very cold. He spoke to me, but he didn’t tell me he was taking the small plane.”

Holly’s body was buried near his home in Texas, with a simple epitaph, “In loving memory of our own Buddy Holly.” But his wife has never visited it. She had suffered a miscarriage after his death, and told Dizon that all she has are fond memories of the man and his music.

Rock musicologist Lillian Roxon wrote extensively about Holly’s impact on pop music in the 1950s and ’60s, “More than any other singer of that era, he makes music that is fun, when sheer animal exuberance was what counted.” Roxon goes on to say Holly had a sound and a style emulated by (and they admitted it) Bob Dylan and Paul McCartney.

Perhaps the more interesting influence Holly had on music was his impact on Waylon Jennings, his bass player during “the Winter Dance Party” tour.

“I was probably the worst rock ’n’ roll bass player in the world,” Jennings admitted 10 years ago. After 1959, Jennings’ country music career blossomed partly because of his notoriety from the tragedy, but also because he paid close attention to Buddy Holly’s sense of rhythm and his dedication to a sound. “Buddy Holly was one of those guys I’ve always said lived in the pocket. When you’re in the pocket you’ve got a rhythm or a melody and it doesn’t stop. He taught me not to compromise, be true to your sound.”

How a moment in time changes lives forever.