We are virtually alone down this back road in northern France. A breeze rustling new spring leaves and chirping birds overhead provide the only sounds here. Nevertheless, because the lawn and flowerbeds look so immaculate, we know gardeners have tended here recently. At a headstone engraved with a maple leaf, our group gathers to listen to fellow traveller Robin John.

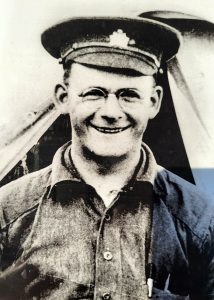

“John Alexander Edward Hughes enlisted in the Canadian Forces on May 22, 1917, five days after his 18th birthday,” she said of her uncle.

Which meant that Hughes was just legally eligible to enlist.

Like so many young Canadians, Hughes felt compelled to serve King and Empire. And since, at the time, he was a medical student at Montreal’s McGill University, the army trained him for the medical corps. He arrived overseas in time to serve in the Arras-Scarpe campaign and earned two Military Medals during the critical last 100 days of the war.

In a moving tribute, Robin John, a retired nurse, said she never considered she had much connection to the military, much less an uncle who served in the Great War as a stretcher bearer. But this cemetery has drawn Robin and husband Tom to join a battlefield tour of sites where Canadians served in the 1914-1918 war.

At Hughes’ grave, she read his letter home thanking his parents for sending a pot of fresh jam, which he admitted was such a delicacy “it was not long in the land of the living.”

Pte J.A.E. Hughes’ headstone simply identifies his regiment, rank and date of death – Sept. 29, 1918 – just 43 days before the Nov. 11 Armistice.

Not all pilgrimages to battlefields in Europe lead to cemeteries. Since the Battle of the Somme in the summer and fall of 1916, a place called Beaumont Hamel has drawn generations of Newfoundlanders to walk this former WWI battlefield, now just grassy trenches, shaded meadows and a towering memorial crowned by a sculpture of Newfoundland’s symbolic caribou.

Gene Fisher’s grandfather, Pte Hubbard J.W. Fisher, sustained wounds here. And he’s considered lucky.

“They lost 86 per cent of his regiment here,” Gene Fisher said, standing beneath the caribou and three bronze plaques commemorating Newfoundlanders whose bodies were never found.

Just after 9 a.m. on July 1, 1916, men of the Royal Newfoundland Regiment had barely gone over the top when they were cut down by German machine-gun fire. Of 800 men, more than 700 were killed, wounded or missing within the hour.

Gene explained that his grandfather had left a teaching job in Bonavista to fight, but overseas faced freezing temperatures in winter, German gas attacks and “if your buddy was killed next to you, his body might remain there for weeks, not removed.”

Despite the odds and shrapnel wounds, Hubert Fisher returned home to Newfoundland and operated a hardware store in Bonavista. For a time, Gene got to know his grandfather there, quizzing him about his wartime experiences.

At some point, the veteran showed his grandson a club he’d used to batter enemy troops in the battlefield, “and there were dark spots on the club, the remains of German blood,” said Gene Fisher, who would himself go on to serve in the Canadian Forces in the 1960s and ’70s.

As the Beaumont Hamel memorial illustrated – commemorating 820 Newfoundlanders with no known graves – all too often in the Great War, soldiers simply disappeared to be commemorated only in spirit – 11,285 at the Vimy Memorial, 72,000 at the Thiepval Memorial, and 54,000 at the Menin Gate in Ypres, Belgium.

Eventually, our tour group, led by Tish MacDonald, followed Carol Pearcey into the Berks Cemetery Extension outside Ypres. The Uxbridge Royal Canadian Legion Branch 170 member entered the vast rotunda there to seek out the name of her great uncle, James Hutchison, on the wall of disappeared dead.

The Black Watch private from Scotland was an old man by most First World War standards, at 44, when he vanished on May 9, 1915. But as Jamie Herriot from our tour group made a pencil tracing of Hutchison’s name on a sheet of paper, Carol Pearcey admitted, “I’ve always wanted to come here to pay homage, even if they never found his body.”

When Robin John finished her pilgrimage to the Bucquoy Road Cemetery, days before, she reflected on the futility of her uncle John Hughes’ death at age 19 on the verge of a budding medical career in 1918.

“An extreme tragedy that he was lost so young,” she said, “and with so much potential.”

So, might it be said of all 59,544 members of the Canadian Expeditionary Force who died in the Great War.

thanks for the commentary Ted. it was a great journey.

It was a memorable tour with my son Jamie, a bucket list endeavour for sure! I can’t imagine it being so without your contribution! Special thanks to Tish & Mike and Tish for organizing and scheduling!🇨🇦🇨🇦🇨🇦