I’d got lost in the main square at Ypres, Belgium. I’d asked for directions from the man at a reception desk inside the town’s massive Cloth Hall. As I thanked him for getting me reoriented, I asked him about the story of Ypres’ recovery and restoration after the Great War in 1918.

“You know that the war levelled the city, yes?” I nodded, and he continued. “It was the forethought of the mayor and aldermen and others that saved our city after World War I.”

“I’d heard that,” I said.

“They gathered all the diagrams of buildings in Ieper (as Belgians call Ypres) and hid them in France,” he said.

The history of Europe, I have learned, has always been fraught with wars – the Napoleonic Wars, numerous civil wars, the Great War and the Second World War to name a few. Indeed, yet another war now consumes Ukraine along its frontier with Russia. And not only have these massive conflicts killed countless millions of people, but they have also repeatedly decimated the continent’s rich cultural heritage.

In August 1914, when German armies invaded Belgium from the east, Ieper had no mechanized industry whatsoever, but housed a thriving linen trading centre, the largest non-religious gothic building in all of Europe. The Cloth Hall, as well as displaying classic medieval architecture, housed frescoes by some of the country’s greatest artists and dominated the horizon with its three-blocks-long main hall and a towering belfry.

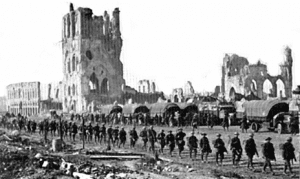

Beginning in November 1914, however, as Allied armies dug in along the Western Front to defend Ieper, German artillery homed on the belfry and systematically bombarded the town, 10 to 20 shells falling every minute.

“The most famous monuments of the town, Cloth Hall and St. Martin’s Church were ablaze,” wrote authors Dominiek Dendooven and Jan Dewilde. “The entire town centre was wiped off the map.”

When the Great War ended, Allied victors wanted the shattered Ieper preserved as “Holy Ground,” or left in ruins as a symbol of the cost of war. Enter Jules Coomans, a Belgian-born engineer and after 1895 Ieper’s town architect, who pursued the restoration of Ieper’s heritage as his life’s work.

It was Coomans and his civic colleagues who’d removed the town’s plans and schematics to France for safety, and then convinced Ieper’s citizens to rebuild a modern town – of houses, shops and navigable streets – but also to restore the town’s gothic heritage exactly as it was. Coomans died in 1937, just as St. Martin’s and the Cloth Hall restorations were nearly complete.

The job of safeguarding cultural heritage amid the ashes of war continues even today. During my recent trip overseas, I learned about the work of contemporary cultural heritage experts – practitioners of a modern Jules Coomans philosophy of preservation and restoration.

In Paris, I caught up with an old friend, Colin Kaiser, for the first time in 36 years. We attended Agincourt Collegiate together in the 1960s; professionally I chose journalism while he earned a doctorate in cultural history.

During our reunion he shared some of his experiences working at the vanguard of UNESCO cultural preservation efforts in the Balkan region during civil war there in the 1990s, then similarly in the Middle East as the Americans invaded Iraq in 2003. During one attempt to enter Dubrovnik, Croatia, he told me his group came under fire, “seeking shelter in a monastery while hoping none of those around us would be wounded on our behalf.”

Coincidentally, I recently read a story by Associated Press reporter Jon Gambrell, who has followed UNESCO experts into Ukraine, where Russian shelling and bombing has threatened libraries, museums and religious buildings. Gombrell pointed out since the war began in February 2022, that the fighting has destroyed or damaged at least 259 cultural and historic buildings in Ukraine.

The AP story highlights the work of a French engineer and a Ukrainian architect using a Zoller & Fröhlich Imager to create a three-dimensional image of the inside of Kyiv’s All Saints Church. “It’s a critical moment,” one UNESCO official said. “If (these cultural places) are not protected now, we really risk that this heritage is lost forever.”

More haunting than even the potential loss of cultural buildings and artwork in Europe, however, is the intent that lies at the base of such destruction. My friend Dr. Kaiser remembered the chaos of war in the Balkans and the indiscriminate vapourizing of churches and mosques and their faithful. What haunted him more traumatically was the madness of “overt ethnic cleansing.”

Not even the lifelong dedication of a Jules Coomans, of my friend Dr. Kaiser, or the 3D image-makers in Ukraine can preserve in the face of such deep-rooted hatred.