About an hour into the tour, I discovered one of the secrets to Canada’s military capability at sea. The tour aboard HMCS Vancouver, a Royal Canadian Navy (RCN) frigate currently in a short-work period at the base just outside Victoria, had taken me through the operations room. I’d sat in the commander’s chair on the bridge. Then I’d seen the ship’s massive rudder system.

I happened to pause at a rack of fire extinguishers, helmets and gas masks. In the event of a major fire at sea, I asked, were the people assigned to fight fires on board the ship former civilian firefighters?

“No,” explained Lieutenant (Navy) Konnor Brett. “Every member of the crew is a trained firefighter.”

And I realized immediately that teaching all RCN sailors to fight fires had nothing to do with personnel limitations and everything to do with practicality. If a warship couldn’t depend on every man and woman in her crew to quell fires, keep the sea from swamping the ship in gales or combat, and deliver basic first aid or rescue tasks, its effectiveness would be severely diminished at sea. “It’s a matter of the ship’s survival,” Brett said.

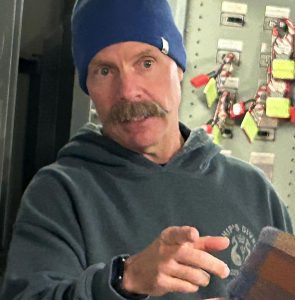

On a recent business and pleasure trip to B.C., I contacted Konnor Brett (we’d met last May during Battle of the Atlantic observances at CFB Halifax). He gave me, some family members and friends a tour of HMCS Vancouver. The son of a Second World War vet, Brett grew up in B.C., joined the Navy League Cadets while at school, and served as both an army and navy reservist while working as a B.C. correctional officer.

Then, in 2006, he joined the navy’s regular force full-time. Aboard RCN frigates he’s now qualified to instruct as a naval warfare officer, navy diver, and boarding party supervisor. Perhaps more important than all his official capacities, Lt Brett is an extraordinary ambassador for the Canadian Navy.

Once my tour group had cleared the security gates at CFB Esquimalt, Brett led us on a bow-to-stern tour of the frigate before she redeploys for operations in waters around the Pacific Rim. Moving about the ship meant stepping carefully along narrow gangways, through hatches and down steep ladders. (It helps to be shorter than six feet tall as a sailor.)

We civilians climbed down those steps facing the ladder and holding onto its railings securely. “In a call to action stations, we’ve all got a mental roadmap and muscle memory to get us where we need to be quickly,” Brett said. “I can get from my officer’s cabin to the bridge (about 100 yards) in 20 seconds.”

On the bridge, Lt Brett explained the chain of command, who sat where, and the way orders were passed. Somebody asked where the ship’s helm was located (we all imagined since the ship was 400 feet long, the helm would be a huge wheel of some sort). Brett pointed to a computer screen representing the ship’s propulsion systems and a joystick on a console.

Also, where there once stood a large circular dial on the bridge, called a Pelorus (or engine order telegraph) ringing out “full ahead,” “slow” and “all stop,” there was instead a row of plastic buttons that could instantly accelerate the ship to top speed. And what’s top speed we asked?

“That’s top-secret,” Brett said, “but unofficially, more than 29 knots.”

Not a secret was the increased presence of female crew. Along the frigate’s corridors, we spotted signs that identified female living quarters. Each was marked with a sign, telling all men entering to shout out, “Man on deck!” (The signs said “Woman on deck” in the opposite situation.)

We learned that women made up about a 10th of the ship’s company. Not because of restrictions against their entry, but largely because recruiters still haven’t characterized careers in the navy as rewarding enough for women.

When I asked Lt Brett what he enjoyed most about navy life aboard a frigate, I figured that he’d say serving in the operations room or on the bridge. “I enjoy going over the side in my diving gear to check and clean her props.”

And the least? He pointed to a coil of rope hanging close to a railing on the open ship deck. “In a man-overboard situation, I’m attached to that rope and in diving gear I jump over the railing down (about 30 feet) to the surface to conduct a rescue.”

While he’s practised the manoeuvre repeatedly, so far Lt (Navy) Konnor Brett has never had to conduct a man-overboard rescue for real. Like everything else in the Royal Canadian Navy, having command of preventive skills is just as important as dispensing the lethal ones.