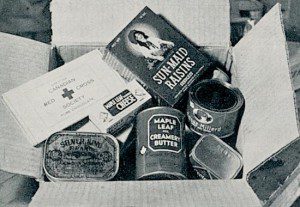

All day long on March 23, the atmosphere was electric across the North Compound. Behind barracks doors – all with stooges at the watch – kriegies collected their forged maps, manufactured compasses and food rations. They stitched them into shirt pockets, jacket linings and pant legs.

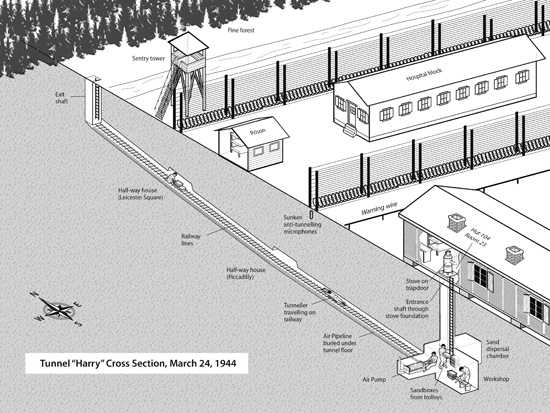

Meanwhile, Robert Ker-Ramsey, staying behind in Stalag Luft III with Tony Pengelly as escape committee veterans, made last minute adjustments underground. He covered the trolley tracks with fresh blankets to muffle the sound, rigged new tow ropes (passed through the main gate by the Vorlager on the premise they would be used for a North Compound boxing ring) on the trolleys, and installed light bulbs (taken from the barracks huts) in every socket available along the full length of “Harry.”

Roommates John Travis (one of the tunnel engineers), Roger Bushell (Big X) and Bob van der Stok, modeled their civilian outfits for Canadian air officer Gordie King. Van der Stok, the Dutch flyer, was going out in the first 20 of the escape order. He emerged from his bunk area in his escape apparel; unlike the fake German corporal’s uniform he’d used during Operation Bedbug, this time van der Stok wore a civilian business suit, handmade by Tommy Guest’s tailors.

“How do I look?” he asked his roommates. “Immaculate,” Gordie King told him.

Pilot Officer Gordon King, from Winnipeg, had arrived just in time for the move from the East Compound to the North Compound in 1943. At 19, in 1940, he knew Morse code, so the air force streamed him into the wireless air-gunner trade, but he was upgraded to pilot training. The RCAF rushed him overseas and sent him, as Second Dickie (observing pilot) on several large bombing operations, including the first thousand-bomber raid on Cologne, Germany, on May 31, 1942. A few nights later, without security in numbers and piloting a Wellington bomber, he and his crew were shot down and captured.

King arrived at Sagan, barefoot, having lost his boots when he bailed out. At the train station he faced the mile-long walk to the compound with nothing on his feet; somebody loaned him footwear he’d never seen before – wooden Dutch clogs. They served him well as he joined the officers’ work crews preparing the North Compound and then later relied on them while working on the tunnel bellows pumping fresh air up the Klim-can air ventilation shaft to the farthest reaches of Tunnel “Harry.”

As the final preparations came together at the base of the shaft to “Harry,” King volunteered to pump the bellows through the night until his turn came, way down the list. Every component in the escape mechanism – no matter how small or large – needed the commitment of every man on the escape team.

“I was a hard-arser,” King said. “I had a map of the area, a little package of food, and my compass just waiting my turn.”